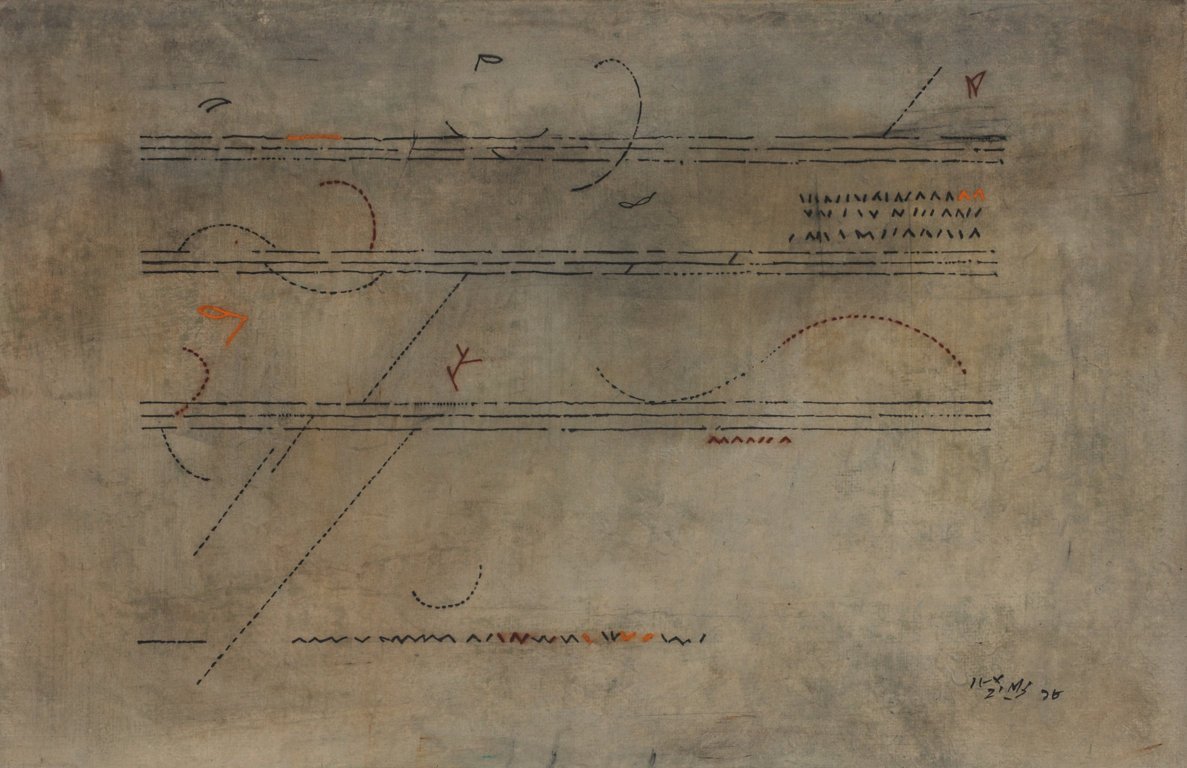

Form & Play by Ganesh Haloi

Asia Week New York 2020

March 12 – March 19, 2020

In his generation of painters, Ganesh Haloi’s practice distinctly stands out for his commitment to abstraction, though he began his artistic training in academic realism, and later undertook the ambitious project of appropriating/painting the composition of the dense narrative frescoes at Ajanta for the National Museum in Delhi. Over the years, Haloi was drawn to the evocation of the land – the paddy fields, the pond and pastures and human settlements, capturing their essence through a language of pristine economy.

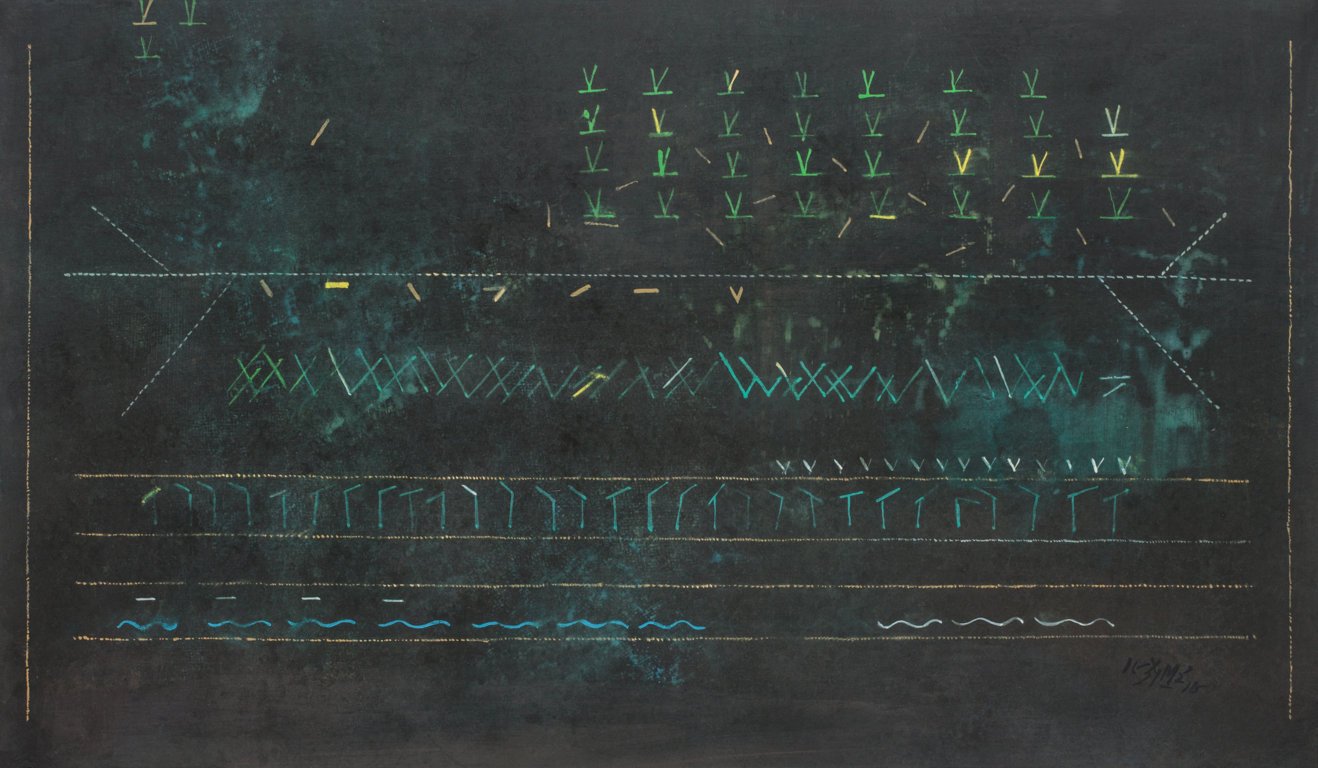

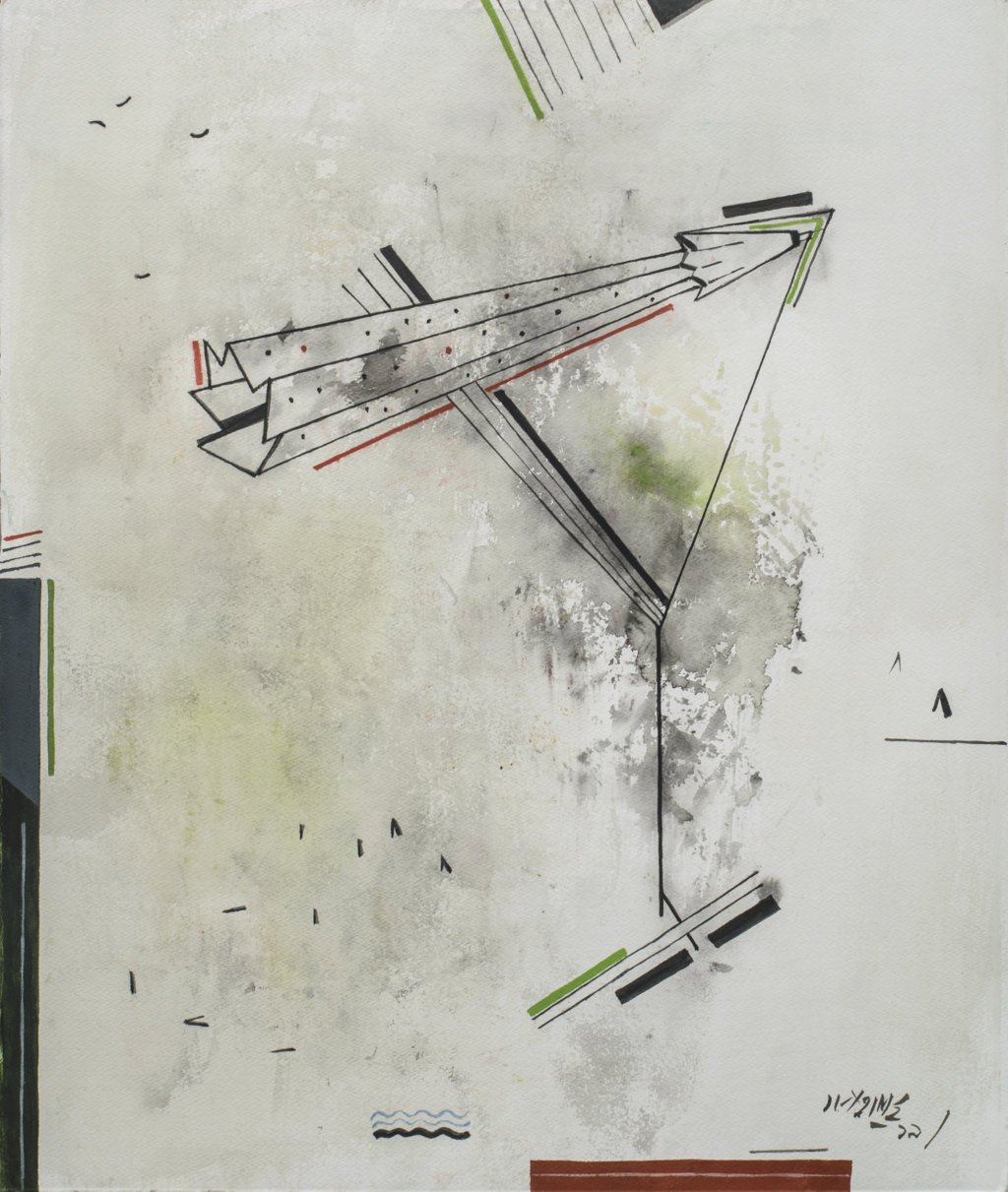

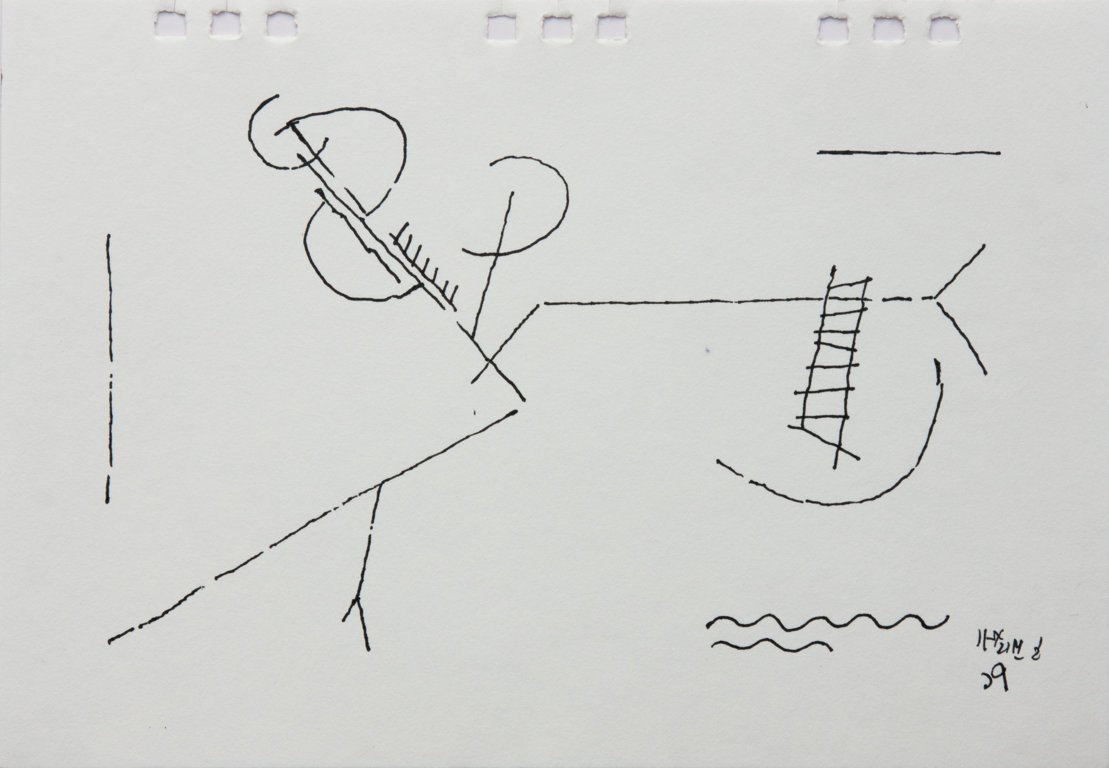

The transparency and delicacy of the verdant greens, the earthy tones, and colours of the sea, exude a rare fluidity. The economy of lines, dots and squiggles gently stroke the surface, capturing the immediacy of a fleeting moment. They transit through an iridescent plane of colour, crossing the line and over the edge, evoking movement that traces the memories of real and imaginary spaces.

One sees a gradual process of freeing the ground of obvious references, reducing complex shapes into abstract planes that intersect at various axes. Born in 1936 in the east of undivided Bengal, Haloi perhaps turned inward to a deeper pain inflicted by the devastation of Partition. Having completed his art education from the Government College of Art & Craft, Calcutta in 1956, he reoriented his artistic practice to suit his temperament. The process of slow working, an even slower aesthetic emerging from working in solitude, through a meditative focus, he makes the viewers enter the realms of the mysterious and the intangible.

- Roobina Karode

Chief Curator & Director – KNMA, India

‘You cannot imagine how much freedom I enjoy. And because I feel that sense of infinite freedom I can exercise that to create my own land. It is my own world – parallel to and different from what you call reality.’

Beyond these intimate moments of creation and personal engagement Ganesh Haloi occupies a significant place in the history of post-independence modern Indian art. Historically speaking, he happened to have chosen an artistic trajectory that is exceptional not only because of his stylistic innovations but also in terms of concerns and content. His art characteristically makes him a sort of loner yet he is very much a part of the history that has encouraged the artists to eschew preset agendas and embrace subjectivity. Bengal artists of the post-independence era, who moved beyond the traditionalist-modernist binary and negotiated the cross-currents with contemporary concerns rather than ideological choices, were by and large figurative artists with various degrees of representational indexes. Ganesh Haloi is one exception who despite his initial figurative works gradually drifted towards non-figurative images and eventually became one of the most sought-after abstract painters from his generation. His paintings are about the compelling world of nature as much as they are about the autonomy of image making. From broad colour fields to minuscule dots and calligraphic lines – the entire range of visual vocabulary in Haloi’s works is played out in a way that on the one hand they function as pictorial signs and on the other as evocative marks. This ambivalence empowers Haloi to explore the possible nuances both at the experiential and metaphoric level. Interestingly, Haloi owes his tonal understanding to his painstaking study of traditional Indian murals at Ajanta. The refinement of his art and the subdued appeal of his paintings can also be attributed to the reticent character of traditional painting although he gives them a modernist turn by accentuating its formal edge and pairing down the image to bare essentials, stripping the composition off the narrative substance. What he is left with, as far his association with traditional Indian painting is concerned and as it is conspicuously visible in his drawings and paintings, is essentially the joy and pleasure of visual composition integrally woven into his deep sense of pathos and melancholy as well. Both the transient and the eternal have been turned into magnificent visual metaphors and unique graphic insignias.

His evocative abstractions in semi-opaque and translucent colours encode an elegy of lost landscape, a nostalgic poetry, and a mapping of the poignant past either radiating a bliss or frozen into a pensive mood. Unlike Kandinsky who deliberately courted obscurity as part of his visual language Haloi’s art is extraordinarily lucid and coherent. The transcendental quality one feels in Haloi’s works is embedded in the very perceptual logic and pictorial making of his paintings. The viewer is enchanted by the sheer dexterity acquired by the artist over the decades involving meticulous research and practice on the techniques and methods of gouache and paintings. Though his paintings follow a reductionist, non-mimetic and often symbolic idiom they essentially embody a poetic and lyrical vision – poised between the seen and the sensed.

As one gradually engages with his paintings one is inclined to feel that the abstract in his works exists more as a tendency, as a linguistic strategy and certainly not as an aim, not as a final realization. It is therefore not surprising that Haloi is never willing to attach the term abstract to his works either as a stylistic category or as an aesthetic nomenclature.

‘I can sense, feel and even see everything out there and in my works. Not only the tangible physical world and its nurturing forces but I can also see the elusive atmospheric elements – the ethereal ones like the wind, air, light, darkness, sound, resonance, silence, movement, vibration, rhythm everything. You can find all these elements in my works.’

- Soumik Nandy Majumdar

Professor of Art History, Vishva Bharati University, Santiniketan