Tapas Konar

January 15 - January 31, 2007

The record of progression of the early medieval Ardha-Magadhi Prakrit to as yet undifferentiated Eastern Indo-Aryan language is contained in a 9th to the 11th century body of literature, generically called the Charyapadas or the Charyageetas.

Composed by Mahayana tantrik siddhacharyas, these padas or geetas are written in a translucent language which the older litetrary historians termed as sandhya-bhasa or the twilight language. The verses, often evoking visual imagery, are frequently suggestive of other imageries. Besides that, not only do the padas contain ambiguous words with other meanings but also double-etenders tangentially referring to physiological facts.

Inspired, as Tapas Konar is, by the language use and meaning potential nexus of the Charyapadas, in his present suit of acrylics on canvas and dense small works on paper he has studiously avoided falling into literary trap of illustrating the padas narratively, as, even when he constructs a fantasy world in his work, he indicates take-off points of his conception of the here-and-now, which is spatio-temporally far removed from the world of the siddhacharyas. Tapas goes back to the Charyapadas to learn the language use of construction of fantasy, as he does to Marc Chagall and to dream imageries of our ancient art.

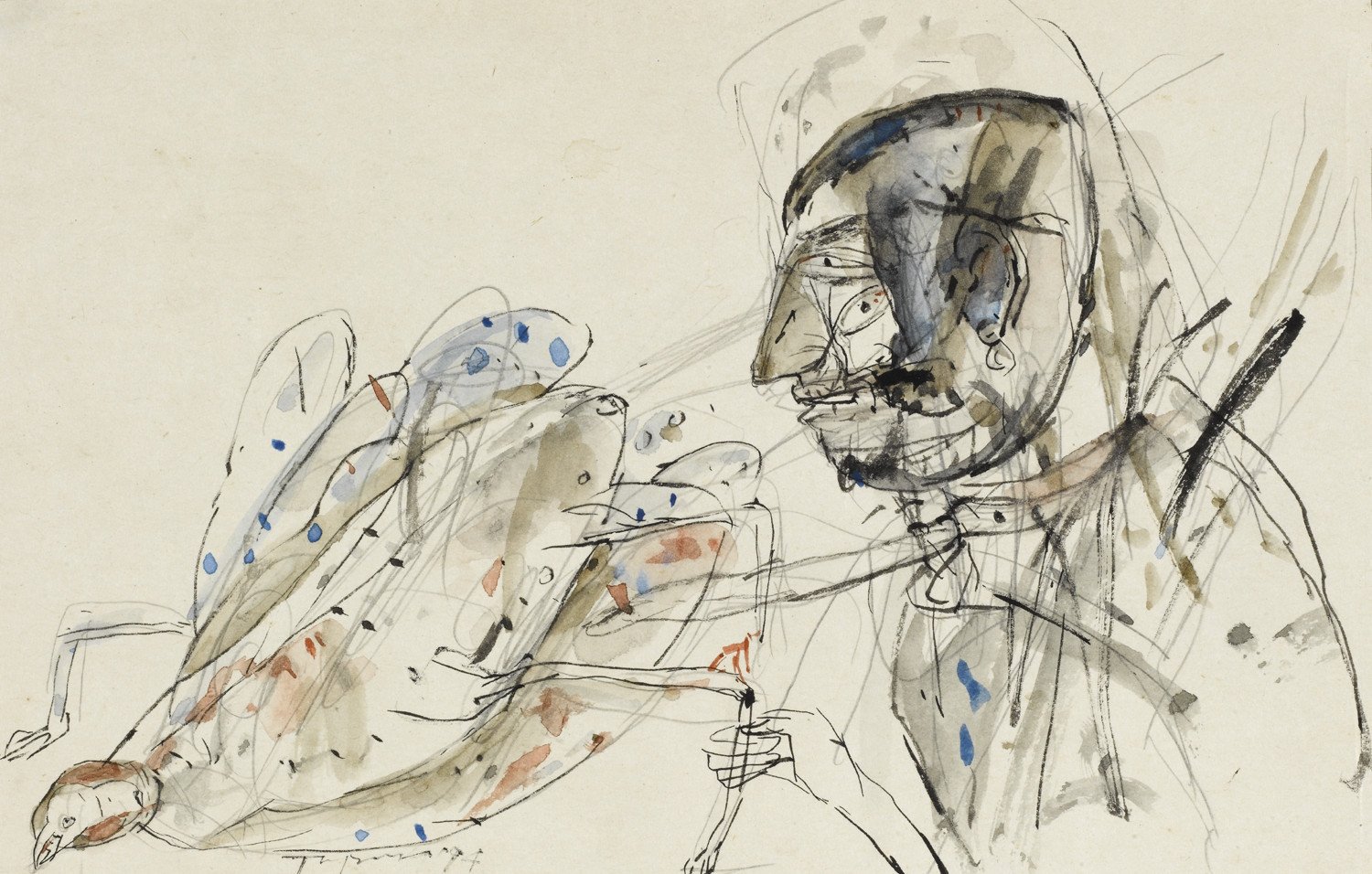

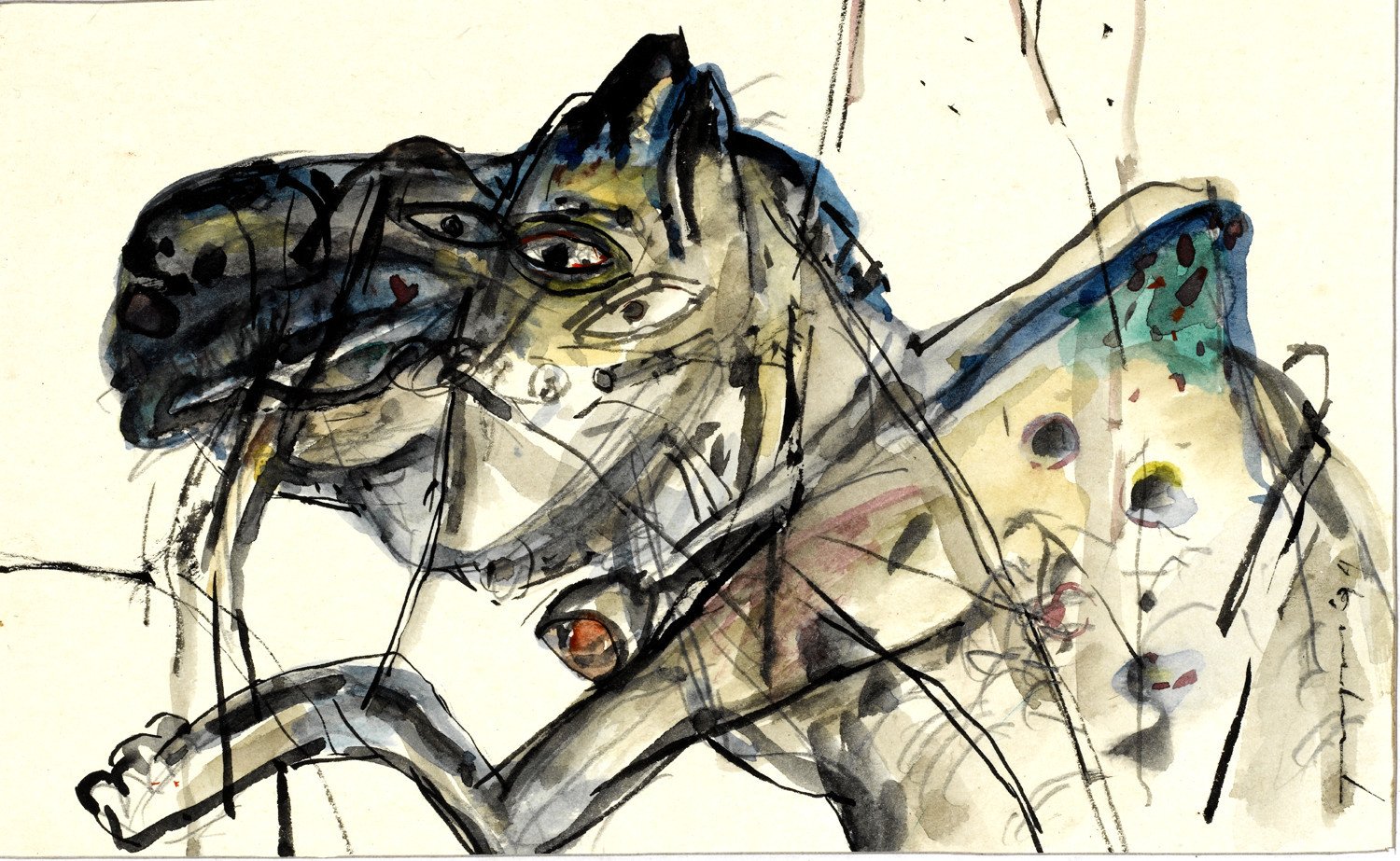

However, in Tapas Konar’s muted use of an overall ambient colour, with glittering gem-like specks of brilliant colours strewn across the pictorial space of each work, Tapas endows a feeling of twilight – dusk or dawn – haze, obliterating viewing of the space as a scene for geometric ordering of objects and events. A perfect scenario for releasing flights of fantasy. On/in such a pictorial space Tapas configurates figures of living beings, mainly genderless humans, indicated by flowing lines only, without mass. With translucent bodies beings of Tapas’ paintings appear weightless; boneless they ambulate at will with their jelly-like physique and float around effortlessly. Yet, their nubile postures and posturings are suggestive of reciprocal gestures. The reciprocity of gestures between figures tend to suggest narrativity, however, without recourse to full length narration. This non-narrational suggestion to narrativity is achieved by spatial configuration of images. Tapas often resorts to multiplication of human physical features in close-succession to indicate bodies in motion, in Dadaist-Futurist mode. But much more potent is Tapas’ manner of super-imposition and inter-penetration of different figures, and thereby distancing pictorial events from real life situations to the realm of fantasy.

Even though non-specific iconic images, reminiscent of known Puranic and Buddhist icons and symbols like the elephant in Mayadevi’s dream (seen so much in Buddhist art), Tapas’ art cannot be termed as mythic, not to speak of mythological. He only invokes mythic associations to load conceptual values into images, just as an icon does. In similar vein he quotes flying figures from Marc Chagall, musicians from Mughal miniature, figures from Turk miniature etc. to invoke associations of flights of imagination. But Tapas quotes so discretely and blends the loaned elements so seamlessly into the fluid rhythm of his work that the intellectual input remains to be deciphered.

A decade or so back, this scribe had described Tapas as a sadarthak uttaradhunik or a non-derivative post-modernist painter. Had not postmodernism freed the artist from the hegemony of the universalistic pretensions of high Modernism, the invocation of a non-living heritage for enlivening a personal mental response to lived reality would not have been possible. Tapas’ distinctiveness as an uttaradhunik painter is that he neither has to construct abstruse ill-communicable symbology nor has any need for plagirising products and processes to vivify a pseudo-personal concept. He exercises his choice to choose from and/or refer to traditions with meaning potentials. Tapas employs his music-attuned senses to bind disparate segments of his painting in rhythmic free flow, endowing his work with a rare kind of musicality.

Pranabranjan Ray

Tapas Konar | Doverlane music conference 2005 | Gouache on handmade paper | 17.75 x 12.25 in | 2006

Tapas Konar | Mystery journey to Ajanta | Gouache on handmade paper | 17.75 x 12.5 in | 2006

Tapas Konar | Pineapple farmer | Acrylic on canvas | 30 x 36 in | 2006

Tapas Konar | Soap fish in bathroom | Acrylic on canvas | 30 x 36 in | 2006

Tapas Konar | Sky Elephants with banana tree | Acrylic on canvas | 36 x 42 in | 2006

Tapas Konar | Jump from a body to a local space | Acrylic on canvas | 48 x 48 in | 2006

Tapas Konar | Connecting Silence Zone | Acrylic on canvas | 48 x 48 in | 2006

Tapas Konar | Remembering red warmth | Acrylic on canvas | 48 x 48 in | 2006

Tapas Konar | Melodrama of killing an innocent Elephant | Acrylic on canvas | 48 x 48 in | 2006

Tapas Konar | Purple on Rope: A blurred Turkish miniature | Acrylic on canvas | 48 x 48 in | 2006

Tapas Konar | Priest & insect | Acrylic on canvas | 48 x 48 in | 2006

Tapas Konar | Musique | Acrylic on canvas | 60 x 60 in | 2006

Tapas Konar | Painter from Jain Era | Acrylic on canvas | 66 x 60 in | 2006

Tapas Konar | Melodrama - Human Circus | Acrylic on canvas | 66 x 60 in | 2006

Tapas Konar | Misty Queen of a circle | Acrylic on canvas | 66 x 60 in | 2006

Tapas Konar | Drawing on paper | Watercolor | 5.5 x 9.5 in | 1994

Tapas Konar | Drawing on paper | Watercolor | 5.5 x 9.5 in | 1994

Tapas Konar | Drawing on paper | Mixed media | 8.5 x 6 in | 1994

Tapas Konar | Drawing on paper | Watercolor | 9.5 x 6 in | 1994

Tapas Konar | Drawing on paper | Mixed media | 11.5 x 8 in | 2006

Tapas Konar | Drawing on paper | Mixed media | 11.5 x 8 in | 1994

Tapas Konar | Drawing on paper | Mixed media | 11.5 x 8 in | 2006

Tapas Konar | Drawing on paper | Mixed media | 11.5 x 8 in | 2006

Tapas Konar | Extra Relations over a ruined city | Acrylic on canvas | 53 x 60 in | 2006

Tapas Konar | Black dancer | Mixed media on paper | 13.5 x 12.5 in | 1998

Tapas Konar | Light unreal | Mixed media on paper | 13.75 x 10.5 in | 2006

Tapas Konar | Around brown clouds | Mixed media on paper | 13.75 x 10.5 in | 2006