NIRMITI: A GROUP SHOW

October - December 2015 at Akar Prakar, Delhi

To negotiate modernity, while retaining an Indian identity, was the main challenge of post-independence Indian art.

Post- independence Indian sculpture therefore made an attempt to reconcile between the modernist elements of the west and the formal idioms of the tradition of plastic art of the subcontinent. Sculptors like Sankho Chaudhuri contextualized the ‘essential form’ of the 20th century European Sculpture into the primary form of the egg that encapsulates the fundamental of all forms. An exploration of the international trend of modernist formalism i.e. the language of cubism and constructivism became the main practice. This gradually became academic and was absorbed by institutions during the 1970’s. But the single motif of the abstracted figure, which became the norm of modern sculpture on the national scene, was a reflection on the artist’s engagement with the vocabulary of classical Indian sculptural tradition. Works of veteran artist, Sarbari Roychoudhury perfectly fits into this genre of quintessential formalism where structure form, balance and monumentality of classical Indian sculpture strive as the main forces of sculpture. This engagement with the Indian classical genre deepened with an exploration of the indigenous technicalities and a more acute involvement with ‘’native figuration’’ in the works of sculptors like Meera Mukherjee. This artist’s approach like a cultural anthropologist reflected on the sculptural practice that and got defined for a search of an identity. A conscious search for identity made artists visit and revisit tradition as a site and in the process shared their own artistic sensibilities with traditional artisans. On a different line, this search for an identity through the ‘quasi-abstract’ formal practice also took a crucial turn during the 1970s with the works of artists like Nagji Patel. His awareness of the traditional legacy of abstraction leads him to explore organic volumes of formal manifestations in nature. The approach was more towards the search for the ‘sacred’ forms, particularly the phallic icons that stood as a metaphor of the “procreative energy of the universe”. Thus scholars think that the concept of abstraction in the 1970s in India evolved from a, “certain inner quest for the ultimate meaning of life which possibly evolved out of a felt spiritual crises in a materialistic world”. The works of Himmat Shah too reflect this ‘spiritual quest’. His ‘essential forms’ become almost synonymous with meditation. Moreover, an approach that lead to works which are ‘true towards their material’ became a significant factor.

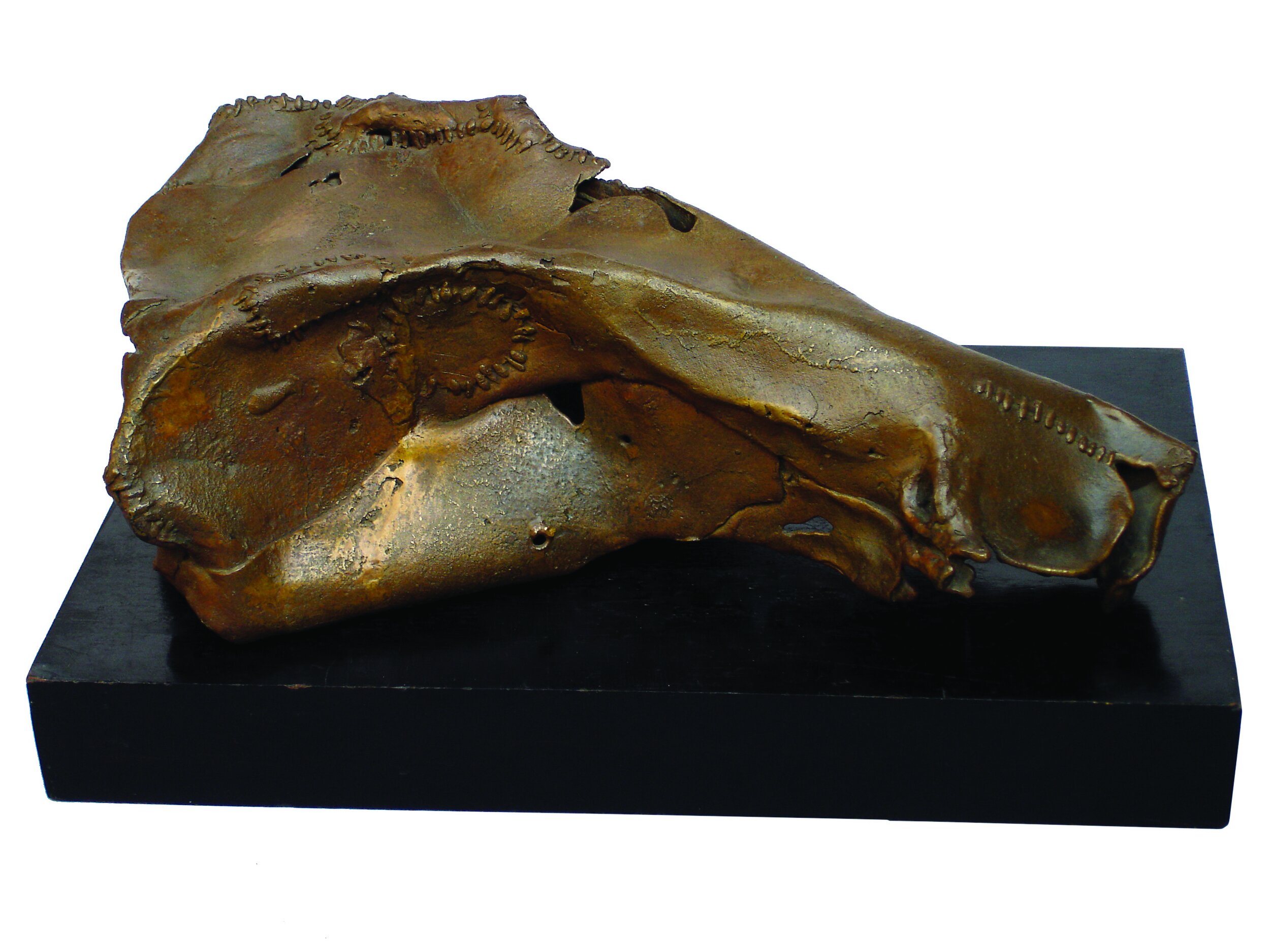

The 1970s and the 80s were also a witness to the initiation of a change of material. This began with the usage of junk. It not only reflected on an industrial culture, that became important at that point of time, but also expressed the sculptors desire to liberate themselves from a ‘formulaic formalism’. A melange of wood, metal, scrap iron and nails broke certain new grounds. Works of Bimal Kundu of this kind form link between a school with a different approach to material and tendency towards creating forms based on a certain realistic/ naturalistic imagery. But a more political approach was introduced with the works of Somnath Hore. The artist’s deep-felt sense of a cultural loss was expressed through the motif of the ‘wound’. His images were a reflection of his impression of the famine, that he carried like an unrepairable scar.

A diverse stylistic approach projecting relevant social, cultural and political issues constitute contemporary Indian sculpture. Moreover, a sensitive handling of the material and a virtuosity in creating the image, in keeping with the demands of the medium, amply compliment the discipline. Virtuosers are P.R Daroz, Aku, Rajender Tiku and Shyamal Roy exhibit a high degree of sensitivity towards the material.

Bimal Kundu | The Buddha | Bronze | 19 x 8 x 7 in

Bimal Kundu | Musician | Bronze | 15 x 9 x 8 in

Bimal Kundu | Dog | Bronze | 32 x 25 x 6 in

Bimal Kundu | Reclining Woman | Bronze | 27 x 6 x 6 in

Bimal Kundu | Bull Head | Bronze | 4.5 x 15.5 x 17.75 in

Sankho Choudhary | Pensive | Brass Casting | 14.6 x 11.6 x 5 | 1999

Sankho Choudhary | Untitled | Wood | 17 x 12 x 6 in

Sarbari Roy Choudhary | Mother & Child | Bronze | 12 x 6 x 7 in | 2001

Sarbari Roy Choudhary | Combing her Hair | Bronze | 8.5 x 3 x 2.5 in | 1960

Sarbari Roy Choudhary | Kiss | Bronze | 7.5 x 4 x 3.5 in | 1975

Sarbari Roy Choudhary | Couple | Bronze | 8 x 4 x 4 in | 1992

Sarbari Roy Choudhary | Ram Kinkar Baij | Bronze | 11.5 x 9 x 10 in | 1964

Sarbari Roy Choudhary | Seated Woman | Bronze | 22.5 x 12.5 x 10 in | 1964

Sarbari Roy Choudhary | Self Portrait | Bronze | 5 x 2.5 x 2.5 in | 1951

Aku | Untitled | Bronze | 27 x 12 x 14 in

Aku | Untitled | Bronze | 38.5 x 15 .5 x 5 in

Rajendra Tikku | Untitled | Terracotta, nail and glazed wood | 10 x 12 x 6 in

Shyamal Roy Choudhary | Girl | Terracotta | 12 x 8 x 5 in

Shyamal Roy Choudhary | Untitled | Terracotta | 19.5 X 23 X 11 in

Nagji Patel | Untitled | Marble & Bronze | 7 x 9 x 6 in

Himmat Shah | Untitled | Terracotta | 10 x 9 x 8 in

Meera Mukherjee | Bou | Bronze | 12 x 6.5 x 5.5 in

P R Daroz | Untitled | Ceramic | 18 x 18 x 4 in

Bimal Kundu | Devi | Bronze | 16 x 22 x 19 in