KAW by Swarup Dutta

November 16, 2018 – December 14, 2018 at Akar Prakar, Kolkata

“A costume, by its nature, is designed to change or enhance the identity of its wearer. In stepping into a costume, you commit yourself to being something other than the character you play each day. It is a transformation capable of changing the mannerisms of the wearer, granting them access to an entirely different life. This may be why extreme fashion choices, which often play with the characteristics of costume, are so frequently adapted by radical individuals in their attempts to challenge the establishment of everyday life.”

It was in my five years of teaching at the National Institute of Fashion Technology, Kolkata that I learnt the transformative power of costume on both body and thereby identity. It was also here that I first met Swarup Dutta nearly two decades ago. He was a young Fashion Design graduate then, much inclined towards photography, and trying to find his feet. We collaborated on an installation-performance project on lost love and longing that I was doing. My brief to Swarup was to create seven male silhouettes using paper patterns as in dressmaking to bring alive seven parallel texts that constituted the performance. As the sole performer, he also dressed me in one of his graduating collection ensembles. The collection was minimal, structured, almost entirely monochromatic, and not gender-specific. The silhouettes were drawn from alphabetical forms, which when worn, obliterated the body. Dressed in what very nearly resembled a white toga, in performance, I had to struggle to rise above the identity accorded to me by my body. Even so far back, Swarup brought a sense of gender ambiguity to a performance that revolved around gender specificity. But then, gender specificity was always against his grain.

In his musings, Swarup comments “It would be great if everyone is both male and female”. The three bodies of work in this exhibition, if viewed in the order in which they have evolved – Khelna-bati, Armour of Weaknesses, and Otherworldly have progressively advanced from a space of androgyny, to the periphery of struggle, to the eventual evolution of the mutant, ambiguous in both gender and identity.

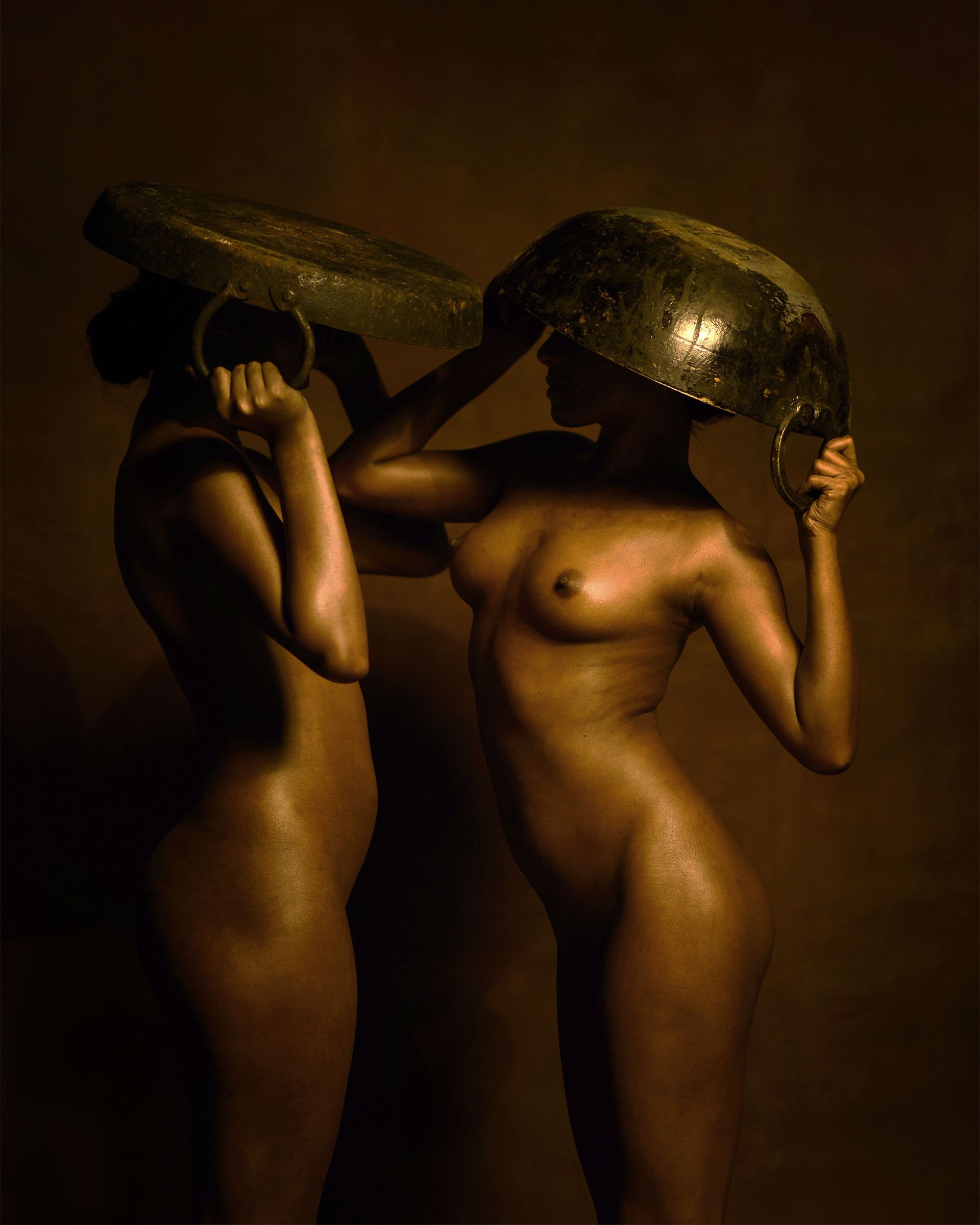

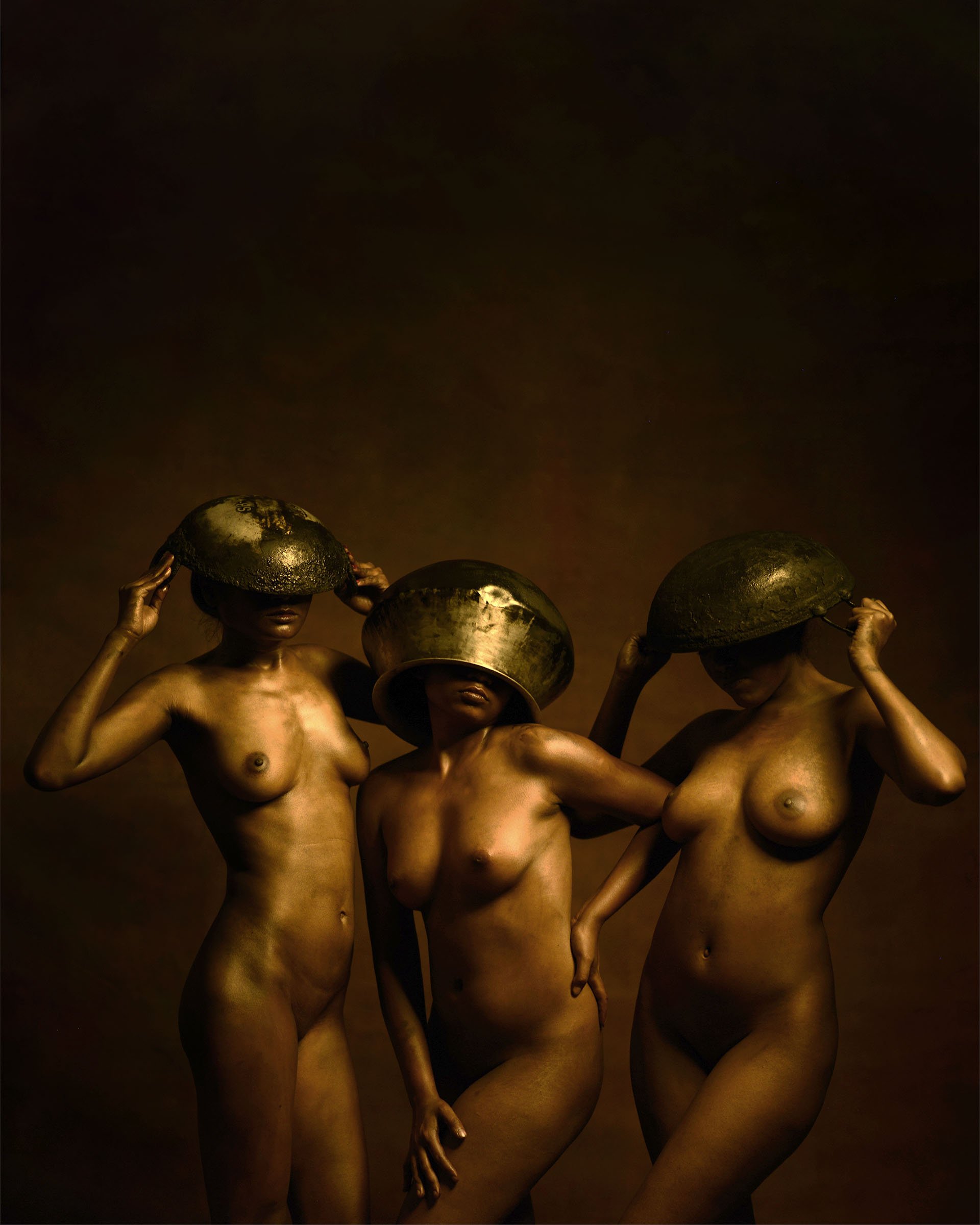

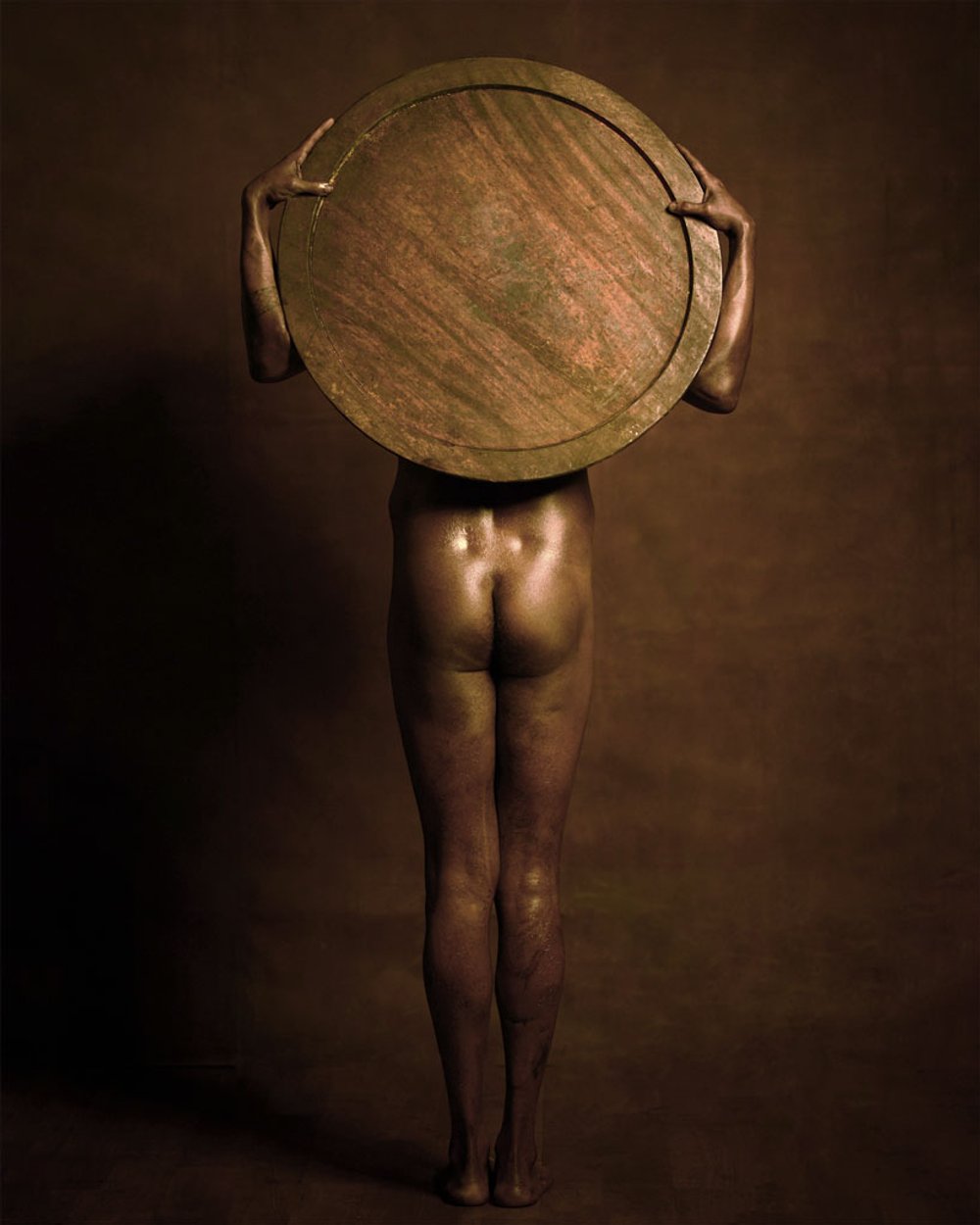

The first series Khelna Bati quite literally translates to “toy utensils”. In Bengali households, young girls played with “khelna bati” in a simulation of what their mothers did in the kitchen in actuality. In a certain sense, this enabled the girl child to seamlessly slip in to the gender role ascribed to her as she grew up. If male children engaged in playing “khelna bati”, it was usually frowned upon as being a gender mismatch. However, Swarup recalls the kitchen, utensils and oil from his childhood with a sense of comfort. “From a perspective of play, as a child, my memories are of being drenched in oil before a bath and being let loose to frolic and play in the sun before bathing in the open.” Here, the artist, in a simulation of memory, drenches his performers in oil and lets them loose in the safe haven of the studio with a set of large kitchen utensils to play with. He assures them anonymity, luring them to frolic and play unfettered games.

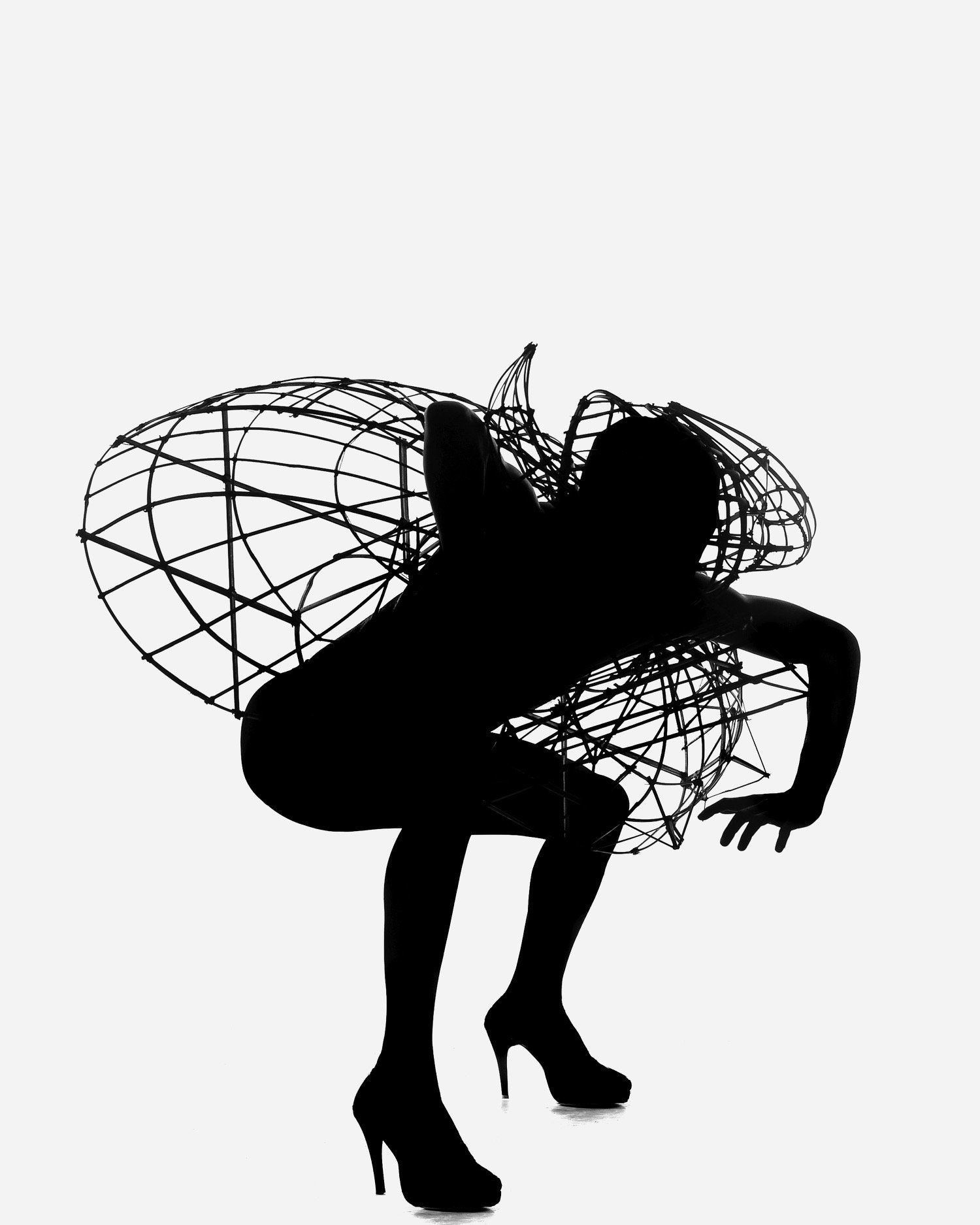

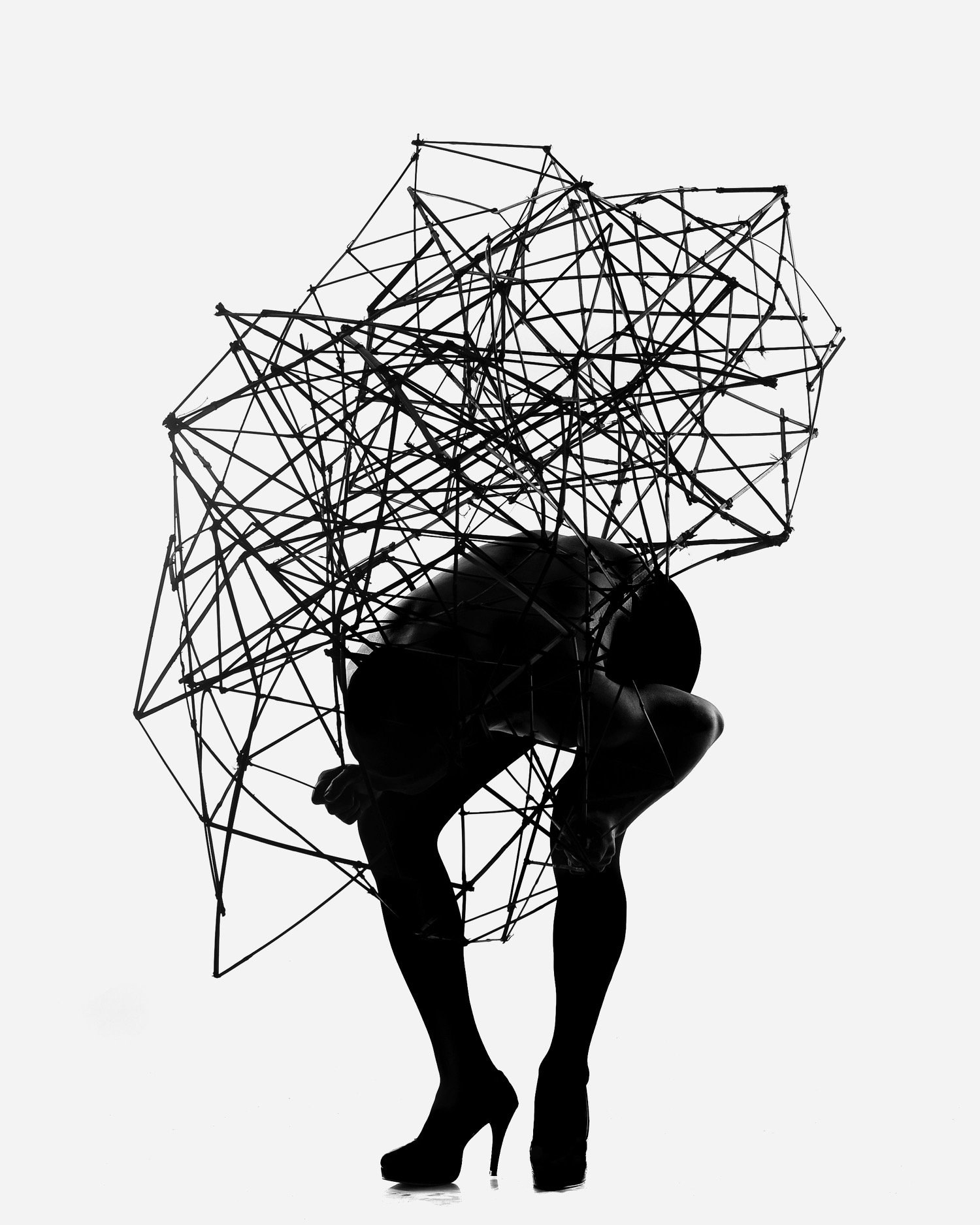

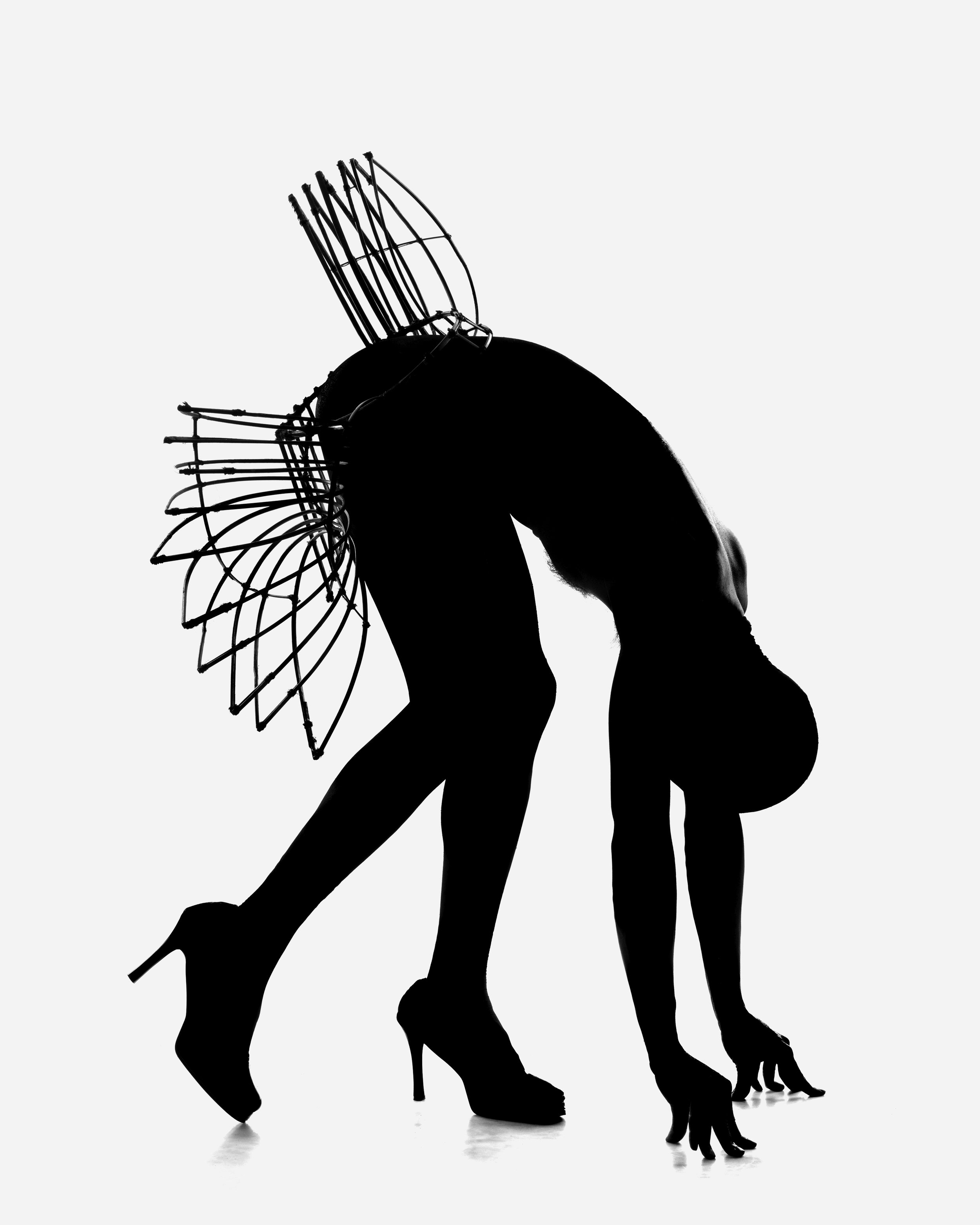

It is interesting to read the works in Armour of Weaknesses in the context of the iconographic precepts of the Shiva Nataraja, constituted as they are of an interplay between the distinctly androgynous body of a dancer and a geometrical construct made up of symmetrical lines into which he attempts to fit himself. The bamboo constructs are sometimes pure geometrical shapes, and at other times reminiscent of floral, vegetal, animal or other organic forms. In interaction with the body, the artist refers to them as “costumes”. Precariously perched on high heels, the dancer twists and turns to accommodate various parts of his body in these costumes, while the artist-photographer rapidly captures his struggle on camera. Once again, the performer is silhouetted in a “nowhere” space, rendering these caged/winged creatures almost like drawings in air, recalling again the fantastic, yet vulnerable creatures of Sukumar Ray’s imagination.

Armour of Weaknesses is further expanded to include an installation-performance of the dancer in interaction with the bamboo constructs, as also a stop-motion animation of the dancer-in-motion.

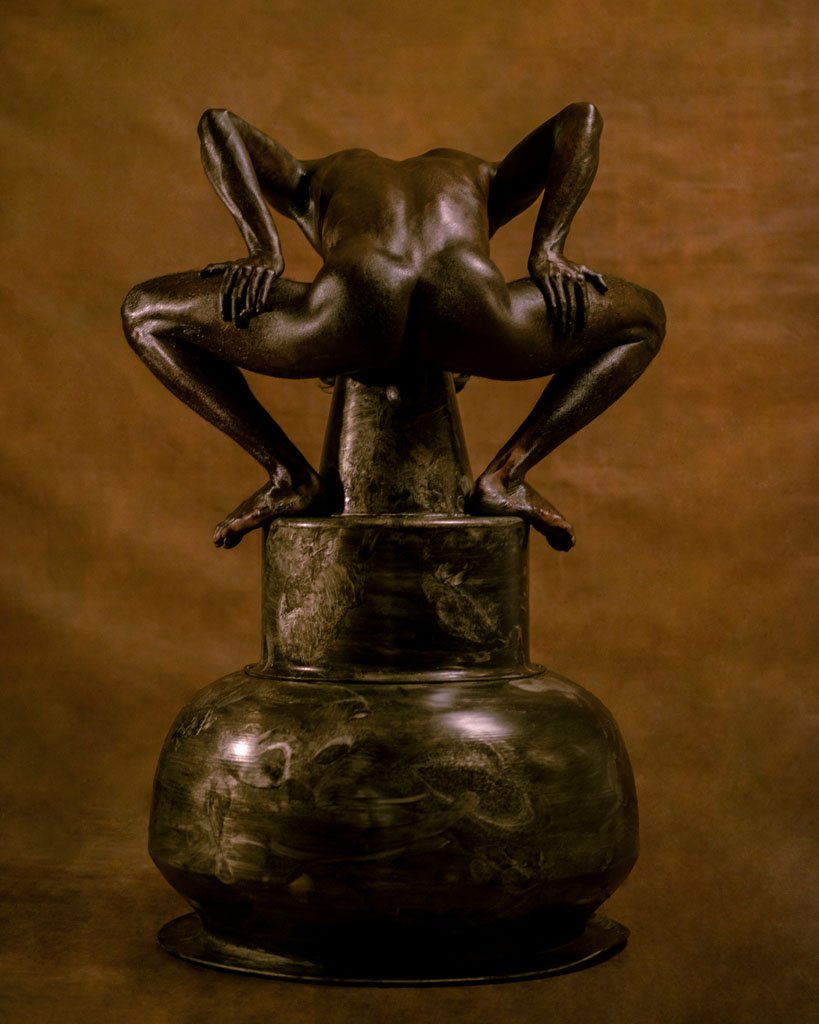

Increasingly, the dancing figure seeks to blur the boundaries between body and costume, seeking to merge the separate identities. In a series of work that emanates hereafter, Swarup gives birth to a mutant male-female form, reminiscent of Harappan mother goddess images, but endowed also with appendages suggesting male genital forms.

“I found these phallic looking gourds in Udaipur and Bangkok. I decided to isolate them from their context and use them as implants on human bodies. I wanted to see if I could blur the defined lines of sexual identity, as we know it” recalls Swarup.

The third body of work is titled Otherworldly. According to Greg French, “For something to be otherworldly, its content or context must be unbound by earthly constraints. It is a space for fantasy and a place for dreams.” He further goes on to say that “Ultimately, we as a civilisation are entering a time that can be classified as post-human, where the fabric of our DNA is changing. Gender has become little more than a social construct, robotics can replace our weakening limbs, and drones now fly side-by-side with birds in our skies.”

Swarup’s last tryst is with nudity, an issue that has threatened to derail this exhibition more than once in an India hurtling towards conservative thought and facist regimes.

To quote the artist, “Our encounter with nudity in India is fascinating. We usually stumble before we engage with this volatile pretension. What does nudity mean within the Indian context? Is it always in the context of erotica that nudity may be discussed? What other ways are there? Playfully nude? Seriously nude?”

These three bodies of work, if viewed in the context of the artist’s enquiries, attempt to confront all these questions. Nudity as seen in the Colonial age in India as a subject of anthropological enquiry, but otherwise treated as taboo. Nudity inherited with ease through India’s religious, social and cultural contexts, but complicated by morality. Nudity as objectification as has been the norm in fashion and photography. And finally, nudity in the space of innocence, to revel in and celebrate.

Dr. Paula Sengupta

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Black & White Prints | 12.5 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Canvas Prints | 39.75 x 32 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Armour of Weaknesses | Canvas Prints | 39.75 x 32 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Colour Prints | 12 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Colour Prints | 12 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Colour Prints | 12 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Colour Prints | 12 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Colour Prints | 12 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Colour Prints | 12 x 9.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Colour Prints | 7.75 x 6.25 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Colour Prints | 7.75 x 6.25 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Colour Prints | 7.75 x 6.25 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Colour Prints | 7.75 x 6.25 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Colour Prints | 7.75 x 6.25 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Colour Prints | 7.75 x 6.25 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Colour Prints | 7.75 x 6.25 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Colour Prints | 7.75 x 6.25 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Colour Prints | 7.75 x 6.25 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Colour Prints | 7.75 x 6.25 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Colour Prints | 7.75 x 6.25 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Colour Prints | 7.75 x 6.25 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Colour Prints | 7.75 x 6.25 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Colour Prints | 7.75 x 6.25 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Colour Prints | 7.75 x 6.25 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Colour Prints | 7.75 x 6.25 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Colour Prints | 7.75 x 6.25 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Colour Prints | 7.75 x 6.25 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Colour Prints | 7.75 x 6.25 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Colour Prints | 7.75 x 6.25 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Colour Prints | 7.75 x 6.25 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Colour Prints | 7.75 x 6.25 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Canvas Prints | 39.5 x 31.5 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Canvas Prints | 16.25 x 13.25 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Canvas Prints | 16.25 x 13.25 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Canvas Prints | 39.5 x 31.5 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Canvas Prints | 31.25 x 24.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Canvas Prints | 31.25 x 24.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Canvas Prints | 31.25 x 24.75 in | 2018

Swarup Dutta | Khelna Bati | Canvas Prints | 39.5 x 31.5 in | 2018

About Swarup Dutta

Photography being Dutta’s primary passion, he has embarked on the journey of image-making challenging the set boundaries of the method in the country. His latest solo exhibition ‘Kaw’ is one such endeavour. He is a Fashion Design graduate from National Institute of Fashion Technology (NIFT), and has passed with a distinction in his Masters Degree in Fashion and Textiles from Nottingham Trent University, UK. He has taught at reputed institutions including NIFT and IICD. Although he began image-making in the year 2002, his love for visual arts informally dates back to 1996. Over the past 4 years, he has created events in Kolkata, moulding perceptions of public spaces within the city by hosting site specific art & design related installations in such spaces. As a heritage enthusiast, he has been actively involved in restoration of old non-heritage tagged houses, appropriating them for suitable activities; one such project being The Calcutta Bungalow, the first heritage bread and breakfast in the heart of north Kolkata. His desire to express himself had surfaced in his school days when he participated in several one act plays, and later has taken him to different mediums, from scenography to styling, graphics to interiors, and crafts to clothes.