JEEVANCHAKRA

January 18 - February 17, 2016 at Akar Prakar, Kolkata

Jeevanchakra, the cycle of life and death, has been elaborated into philosophical and cultural systems across all human societies.

While birth and death are universal phenomena, they are interpreted in ways that are deeply influenced by historic, economic and socio-political conditions of particular places and cultures.

Jeevanchakra presents the experiences of those involved in the transit of the body into or out of the tangible world: healers, midwives, surgeons or family caregivers. It speaks of conceptions of the body informed by gender, class privilege, religious beliefs and the cultural precepts of different communities across India. The exhibition interrogates binary oppositions too easily constructed between modern medicine and traditional healing. It challenges notions of purity and pollution ascribed to women’s bodies, and to those of individuals associated with death rituals. Fundamentally, it also questions whether life, whatever the circumstances, is always preferable to death.

In many Indian communities the death of the mortal body does not mark an absolute conclusion. The relationship between the physical body and the spirit must be severed through elaborate rituals. In order not to pollute air or earth, Parsis neither cremate nor bury their dead but leave bodies to be devoured by vultures in ‘Towers of Silence’. In 1980, Sooni Taraporevala photographed Doongerwadi, the hillside in Bombay where the ‘sky burial’, Dokhmenashini, takes place. More than 3000 years old, it ensures the safe passage of the deceased to the after-life. In the decades since the photographs were taken, cattle were treated with anti-inflammatory drugs that made their flesh toxic to the mighty scavengers. The vultures’ decline, to the point of extinction, has forced Parsis to turn to burial or cremation, leading to spiritual crises for the bereaved and for the community at large. Dokhmenashini also reveals socio-political structures underlying death rituals. The Khandias (pall-bearers) traditionally bathe and carry corpses to the Towers of Silence, and then ritually push them into a deep central pit. Despite belonging to a casteless community, the Khandias live in near-isolation in Doongerwadi, because of their contact with the dead.

Childbirth is deeply affected by traditional practice and by differing access to medicine. Gauri Gill spent time with a dai, a traditional midwife, in a remote village in Rajasthan. Gill had been invited to photograph the birth of Kasumbi Dai’s granddaughter, but ended up also assisting with the delivery. She notes that compared to urban, medicalised childbirth which tends to ‘fetishise the experience of childbirth’, here it was treated with simplicity and ease.

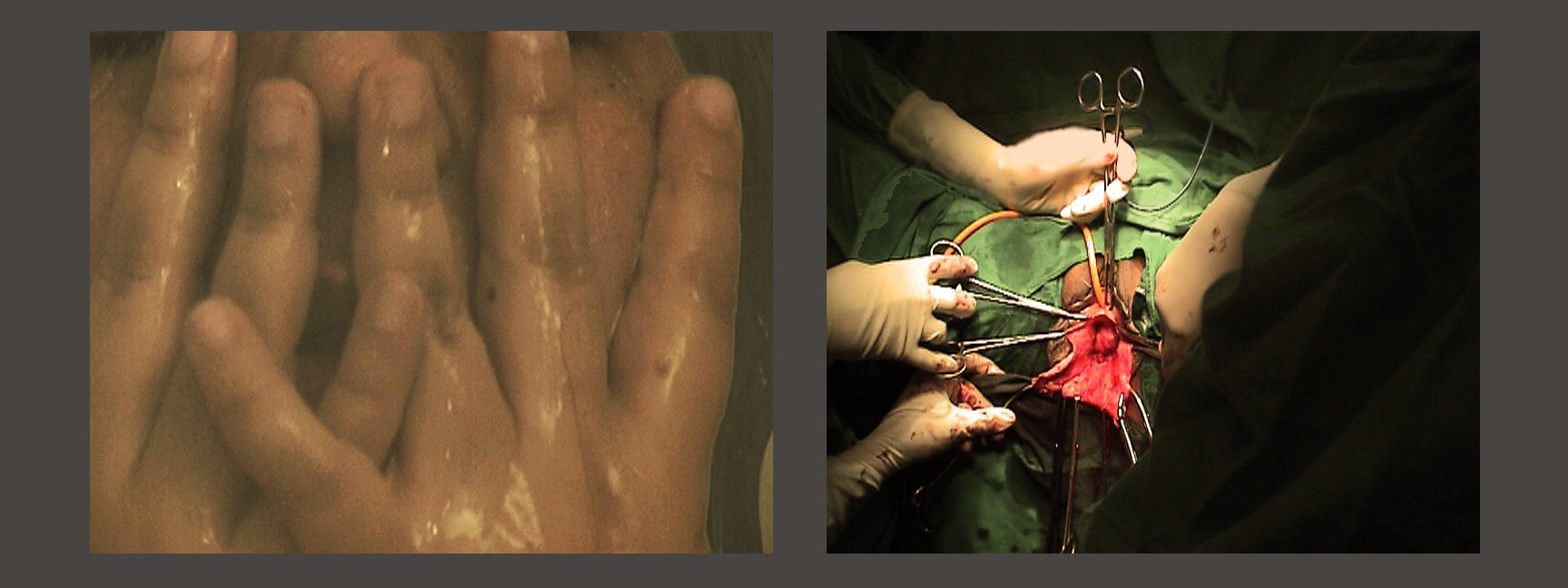

In an ongoing project, Sonia Khurana filmed her mother’s hysterectomy to understand what she terms the ‘cultural destiny of women, i.e. maternity’. Social attitudes and meanings are layered onto female sexuality, reproductive processes and surgical sterilisation. Khurana inverts the common narrative of loss offered by many women who have undergone hysterectomies. Her subjects include those who said they now ‘felt clean’. Her video ‘missing womb’ serves as a prologue to these ‘womb narratives’. Mithu Sen subverts the idea of pregnancy in images of pregnant male bodies, in a critical take on what is essentially a gendered experience - both a privilege and a one-sided responsibility.

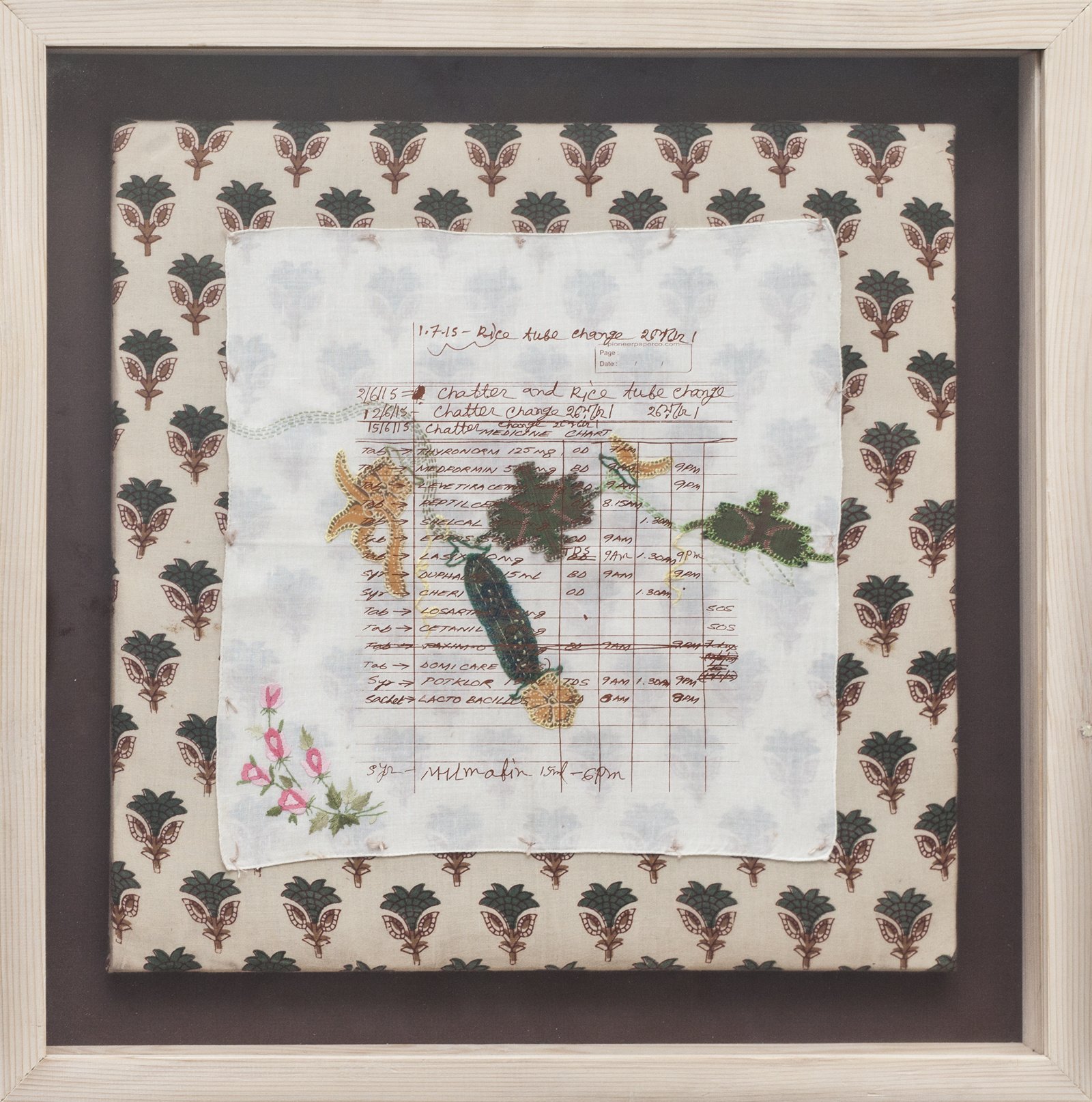

More subject to choice than circumstances of birth are the questions not only of how but also when to die. Reflecting upon her experience of caring for her terminally ill mother, kept alive for over nine months by modern medical systems, Paula Sengupta questions medical science’s inability to address the notion of ‘allowing death’. She writes, ‘While caring for my mother, I was advised to stop food and water to hasten the end – accepted ethical practices in some cultures, while sacrilegious in others.’ Nilima Sheikh too addresses the role of caregivers tending to aging and diseased bodies, in daily rituals of bathing, wiping and dressing.

Anthropologists note that for many communities death is a liminal, social event, marking a transition between lives. Sheba Chacchhi documents the initiation of women ascetics. All outward signifiers of gender, class, caste and family lineage are extinguished as clothes, hair and name are discarded. After three days in which the ‘death rites’ of their previous lives and identities are performed, a ritual bath in the Ganga marks their rebirth. Srinivasa Prasad uses human ash to create a memorial to the unknown dead that symbolizes the impermanence of the body and its identity. Prasad challenges traditional attitudes towards mortal remains, and akin to a Tantric practitioner or an Aghori, he eliminates the taboos associated with death.

Gargi Raina’s sculptural installation, which speaks of being born from eighty-four thousand wombs, draws from the poetry of a twelfth century Kannada woman mystic, Akka Mahadevi. Using an eighteenth century Persian medical manuscript, Raina underlines the need for shafa, or healing, when the connection between body, mind and spirit are wrenched apart not in the natural course of living and dying but through human aggression.

The body and its physical, mental and emotional health are central to how the world is perceived, experienced and constructed. Jeevanchakra hopes to add layers to our understanding of birth, death, and the life of the mortal body.

Arpita Singh

Gargi Raina

Gauri Gill

Gauri Gill

Gauri Gill

Mithu Sen

Nilima Sheikha

Nilima Sheikha

Paula Sengupta

Paula Sengupta

Paula Sengupta

Sheba Chhachhi

Srinivasa Prasad

Srinivasa Prasad

Srinivasa Prasad

Srinivasa Prasad

Sonia Khuranna

Sonia Khuranna

Sonia Khuranna

Sonia Khuranna

Sonia Khuranna