Amber Alleys, Staccato Sounds

February

In the colonial city of Calcutta, once the proud capital of the British Empire, the Indian or Black Town extended upriver, north of the English town.

Clearly distinguished from the European or White Town, it was a teeming settlement peopled by a huge mixed crowd. Its original nucleus was the Great Bazaar (Burrabazaar), surrounded by the Chitpur Bazaar, Kumurtuli or the idol-makers hub, and the historic Ahiritolla and Sovabazaar localities. From babus to boatmen, and printers to prostitutes, the streets of the Black Town bustled with an astounding array of sights, smells, and sounds from the crack of dawn to the dead of night.

In these very streets, Aditya Basak grew from childhood to adolescence in the 1960’s. Even at the time, the serpentine alleys of the Chitpur Bazaar remained largely unchanged, as if frozen in time. People idled away the daylight hours basking in the hazy afternoon sun, enjoying a game of cards, engaging in banter at the street corner, and slowly moving on to perform a chore or two. As the sun set on yet another unhurried day in the Chitpur bylanes, the dappled light slowly turned to amber, lightposts gleaming gold in the dark crevices of the city’s heaving Black Town. As the prostitutes and nautch girls took to the streets, and the echoes of jatra reverberated off the jostling rooftops, the letterpress machines clammered rhythmically to and fro, and the blockmakers of Chitpur whittled away at their meagre livelihoods. The last of the Battala books, treasure troves of forbidden literature, lined the walls of dimly-lit shops, often barely a sliver in the wall. In this peaceful, somnolent world, far removed from the White Town, Basak spent his formative years, enmeshed in a time warp.

Amber Alleys, Staccato Sounds marks the return of a mesmerized, wonderstruck boy to the memories of his adolescence. It also marks the passing of an era – the transition of colonial Calcutta to Marxist Kolkata to Globalized Metropolis, the passage from colonization to globalization. Like all things vernacular, the systematic erasure and consequent annexation of the printing and publishing industry was a powerful weapon in the process of colonization. However, like with much else in Colonial India, the mainstream printing and publishing industry soon spawned a parallel indigenous cottage industry driven by the resurgence of vernacular literature that flourished in the bazaars of the Black Town.

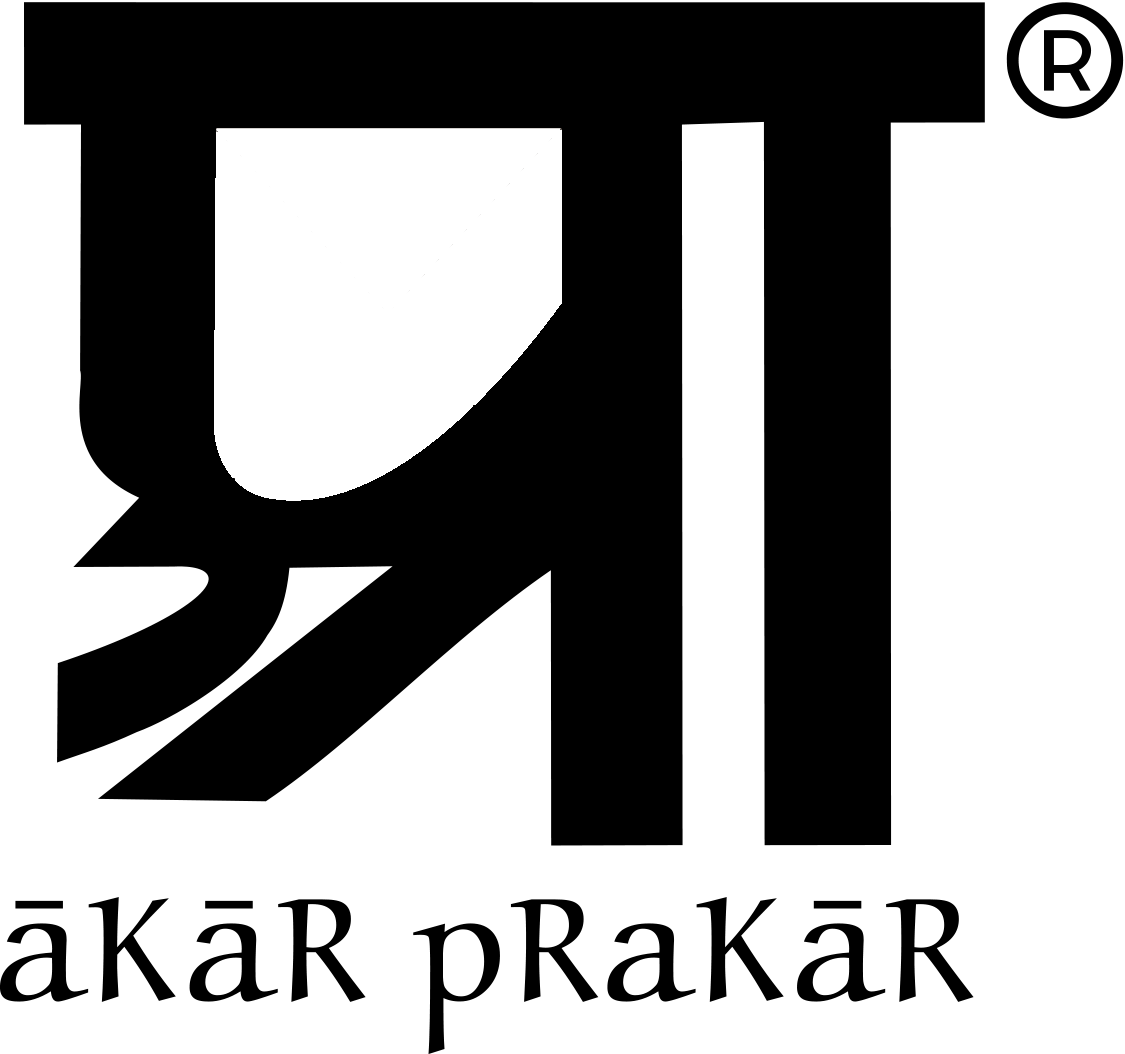

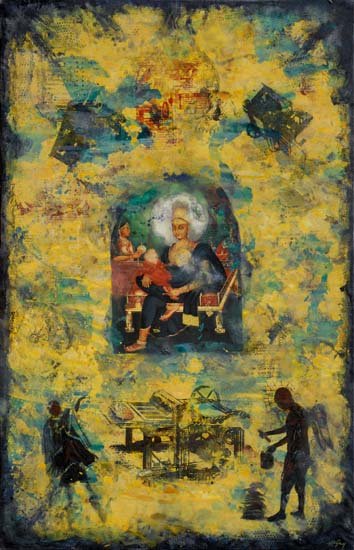

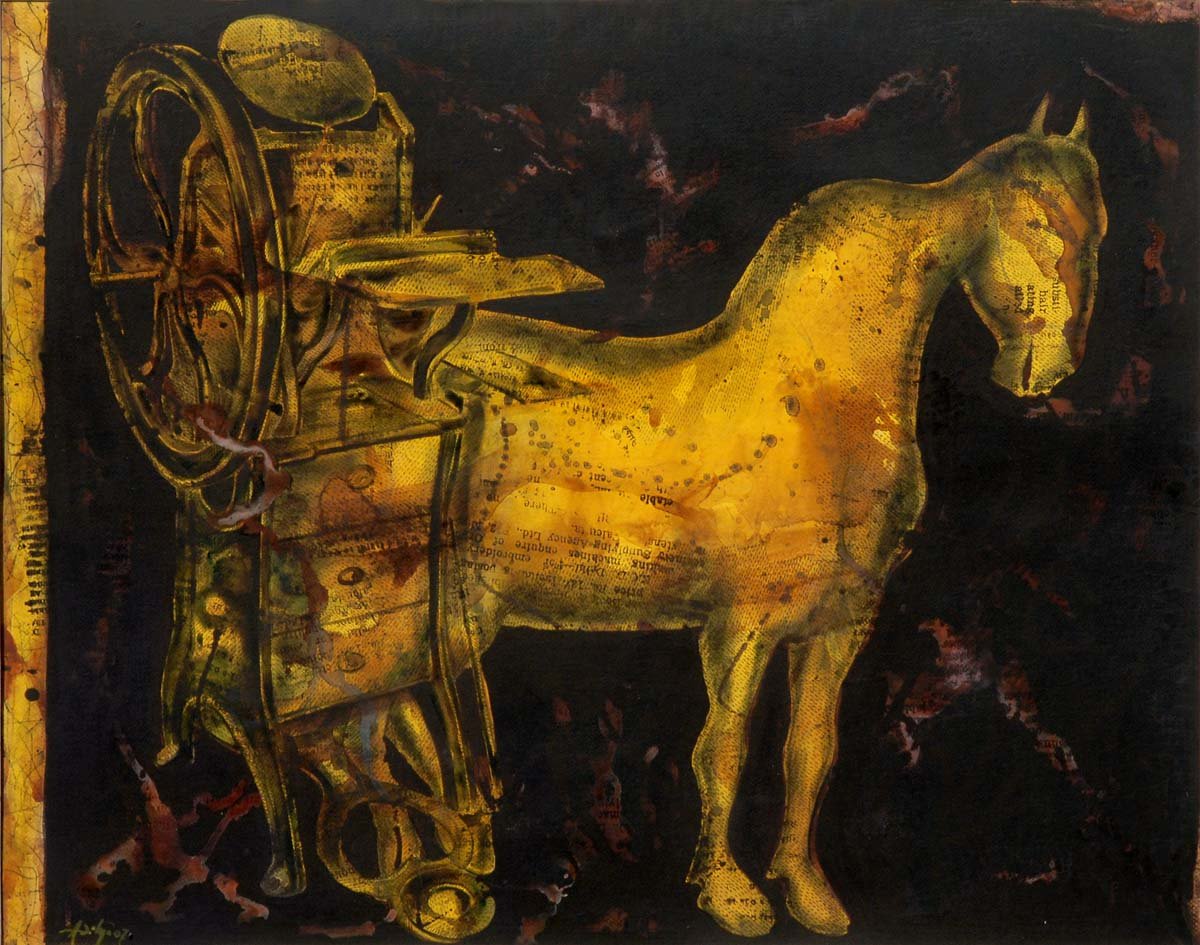

Aditya Basak’s current body of work nostalgically harkens back to this lost era – a time when the tapping of the typewriter, and the clamour of manually operated letterpress and lithograph machines echoed through the streets of Chitpur. In a series of paintings painstakingly illustrating typewriters, treadle machines, and presses of yore, and the many English and vernacular texts that were rolled of them, Basak laments the inevitable demise of the handcrafted and the consequent triumph of the mechanized. Antique presses of every description loom large in picture-spaces otherwise scattered with silhouettes of Europeans and natives in their archetypal roles of colonizer and colonized. Randomly selected texts, barely legible, float behind to form textured backgrounds.

And as the presses fall silent and the type begins to rust in drawers that no longer rattle open, Basak interviews master-printers whose once sought-after skills are today defunct. As the dim lights grow dimmer still, the print shop (here simulated within the gallery space) sinks into near-darkness, the viewer guided only by the fading sounds of the master-printer’s voice as he recounts the heyday that once had been. Through the muffled “klickety-klack” of the letterpress and the flutter of printed paper strung out to dry above, the viewer gropes his way around a black room, picking his way through printing paraphernalia from days long gone by, encountering projections buried under empty type-drawers and in ovals on dark walls – black-and-white videos and backlit texts of the men and machines that constitute the chequered history of printing in the Subcontinent. Even as the viewer tramples upon a colonial coat-of-arms, Bat-tala woodcuts and oleograph prints of Hindu divinities surface beneath advertisements and snippets of news that hearken back to colonial times, each a signifier of the layered inheritance that constitutes the culture of the Subcontinent.

Printing came to India in1556, about a hundred years after Gutenberg’s Bible, introduced by the Portuguese missionaries in Goa. Expected to hasten the spread of Christianity from Goa it spread along the Deccan coast with the Dutch, the French and finally, the British. In British India, it was political impetus rather than missionary zeal that propelled printing forward.

Printing came to Calcutta more than two hundred years after it arrived in India, but the city rapidly became India's first great centre for commercial and government printing. In 1777, James Augustus Hicky established Bengal's first printing press in Calcutta. The Hicky Press, however, printed only in English.16

The whole of the early Calcutta commercial printing trade was organised around the production of weekly newspapers. By 1800, there were forty printers active in nearly twenty presses. Over six-hundred-and-fifty works are known to have been issued before 1801. Towards the last decade of the 18th century, the Hon'ble Company’s Press and several other commercial presses also established type foundries where new fonts in vernacular scripts were cast.

The first Bengali book, N. B. Halhed's A Grammar of the Bengalee Language, was printed in 1778 by the bookseller, John Andrews at his press in Hooghly at the behest of the then Governor General, Warren Hastings. This book was printed from movable Bengali type drawn by the calligrapher, Khusmat Munshi and designed by Company writer and Oriental scholar, Charles Wilkins. He was assisted in cutting the punches and striking the matrices by Joseph Shepherd, a Calcutta engraver, and in casting the type by the Bengali blacksmith, Panchanan Karmakar. The successful printing of Halhed's work led to the acceptance of Wilkins' proposal for the establishment of an East India Company press in Bengal, first at Malda and subsequently at Calcutta.19

By 1798, Panchanan had established his own printing press, which became the centre of printing activity in Bengal. He later joined William Carey at the Baptist Mission Press at Serampore, which made an invaluable contribution to the development of printing in Bengal. Following his death in 1804, his son-in-law, Manohar Karmakar and, thereafter, his grandson, Krishnachandra Mistry continued his work.

The Baptist Mission Press at Serampore, established by Carey in 1800, became the most prolific press in India in the first half of the 19th century. Under Carey, Joshua Marshman and a trained printer from Derby, William Ward, the press produced innumerable publications in more than forty different Indian and foreign languages and dialects. For most of these languages, the Karmakar family designed fonts. 20

The advent of the 19th century saw the beginning of the Bengal renaissance and with it, a revolution of the printed text industry. Several Bengalis of learning and intellect established presses of their own. First among them were Baburam Brahmin and Gangakishore Bhattacharya followed by Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Pandit Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, and Upendrakishore Roy Choudhury.

While European printers were at the helm of all printing activity, an Indian participation gradually came about due to the obvious need for manpower. Initially employed as artisans and craftspersons, Indians are later seen as entrepreneurs and pioneers in printing in both vernacular and foreign languages and as able illustrators. Until the advent of Bengali printing presses in the early 19th century, English-owned presses established since the last quarter of the 18th century, employed metalsmiths and wood-workers from traditional artisan communities to work their presses. It was in these presses that the artisans learnt to put their traditional skills to new applications and also learnt to take impressions.

By 1854, there were forty-six presses in Calcutta printing Bengali works and nineteen newspapers and periodicals. In addition to these were the presses in Serampore, Burdwan, and Rungpore. 21 The Bat-tala area of north Calcutta became the hub of indigenous publishing and printing activity in Bengal. From here emanated a huge volume of mediocre, inexpensive, and often illustrated vernacular literature.

Basak’s is the proverbial “once upon a time …” tale. In a post-colonial, rapidly globalizing city and a state hurtling towards industrialization, there is scant space for history or heritage. Even as a significant chunk of the city’s past is edged out of the meagre niches where it still struggles to survive, Basak attempts to revive interest in the foundations of a once thriving industry that has today entirely altered its countenance, rendering much that is valuable obsolete in its wake.

Dr. Paula Sengupta

Detail 2 - An Old Printing House

Detail 3 - An Old Printing House

Detail 4 - An Old Printing House

Detail 1 - An Old Printing House

Untitled 18 | Mixed media on Canvas | 58.25 x 37.52 in

Untitled 17 | Mixed media on canvas | 49 x 37.5 in

Untitled 15 | Mixed media on paper | 40 x 60 in

Untitled 14 | Mixed media on paper | 40 x 60 in

Untitled 13 | Mixed media on paper | 40 x 60 in

Untitled 12 | 41 x 29 in | Mixed media on canvas

Untitled 11 | Mixed media on paper | 25.5 x 36.25 in

Untitled 10 | Mixed media on paper | 28 x 35.5 in

Untitled 9 | Mixed media on paper | 41.5 x 29.5 in

Untitled 8 | Mixed media on paper | 20.5 x 15 in

Untitled 7 | Mixed media on paper | 20.5 x 15 in

Untitled 6 | Mixed media on paper | 20 x 17.5 in

Untitled 5 | Mixed media on paper | 21 x 18.25 in

Untitled 4 | Mixed media on paper | 26 x 37 in

Untitled 3 | Mixed media on paper | 40.5 x 30 in

Untitled 2 | Mixed media on paper | 20.5 x 20 in

Untitled 1 | Mixed media on Canvas | 58.25 x 37.52 in