3 Masters

October 14 - 23 October, 2008

Drawing, in the etymological sense of dragging, always leaves behind a line or a mark.

It can, be presumed that the art of drawing would be line-based or composed of made marks. In actually, however many things not strictly composed with lines and marks, these days, are passed off as drawings. Excepting the conservative critic, nobody would have objection to the use of other elements of visualization, such as masses, tones and textures, along with disciplining lines, as long as those serve the function of lines. What, however, is the function of the line? It needs to be reiterated that in the phenomenal (visible) world or in the world of nature there is no line, except as illusion created by light and shade on variable planes. The line, ontologically, is a human construct. Lines are drawn and marks are made holistic perception. to graphically indicate concepts and ideas on surfaces. These are not generally made for generating holistic perception. Similarly, a maquette is a sculptor’s sketch (as most drawings on surface are) which she herself needs to clarify her own line of future action. Drawings and maquettes then are brief indicators of intention.

Akar Prakar’s showcasing of drawings of Francis Newton Souza, a pioneer of Internationalist Modernism in the 20th century Indian art and of Jagdish Swaminathan, proponent of spiritual universality and of the maquettes of Meera Mukherjee, an exponent of validity of living traditions in modern art, unintendedly perhaps, highlights the contradictory pulls and pushes, approaches and orientations of modern Indian art.

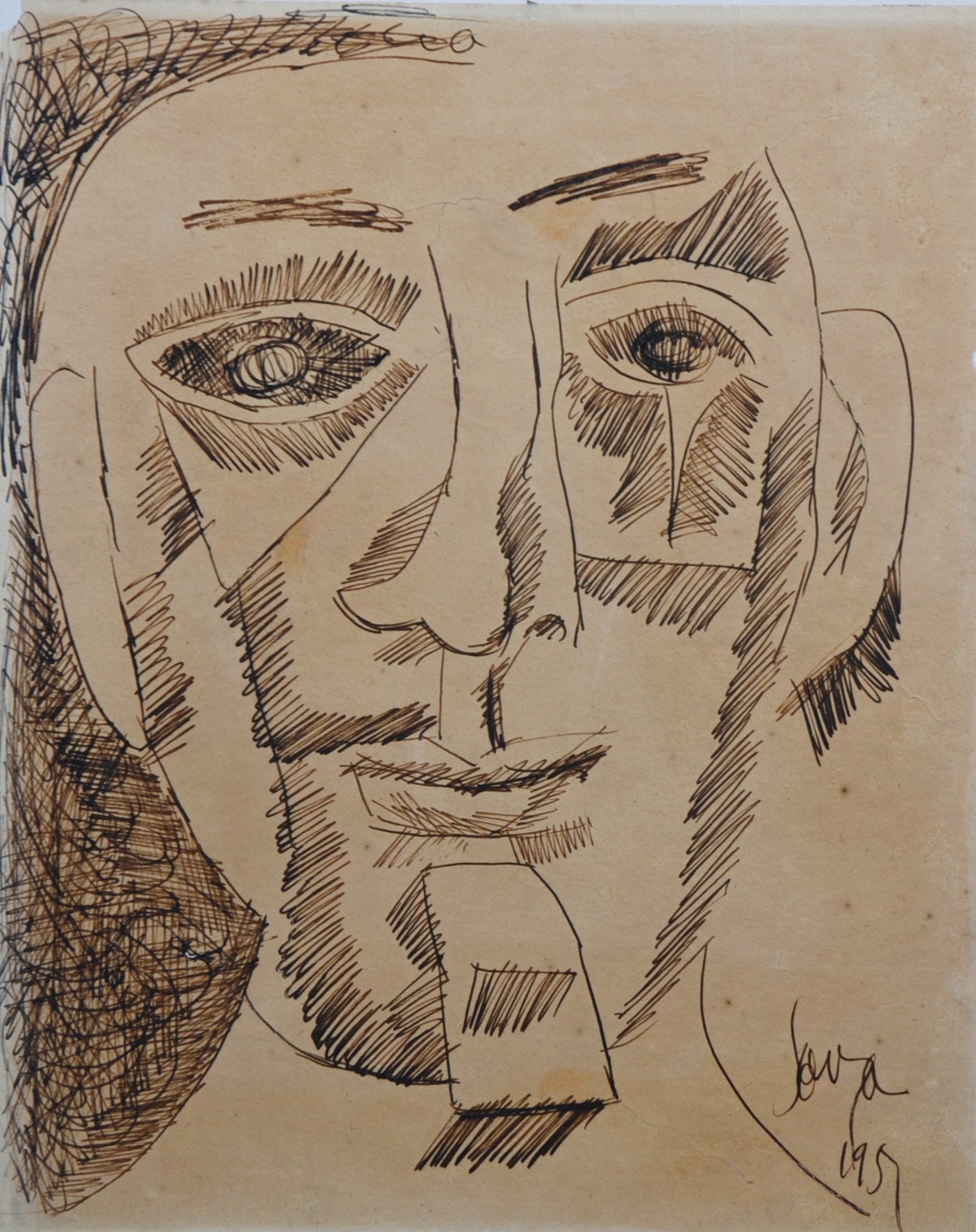

Francis Newton Souza’s creative orientation is an interesting subject of study for the scholars interested in factors governing individual choice in acculturation process, under a regimen of hegemony. As the exhibited monochromatic drawings of Souza, culled from different periods of his creative life, shows that his primary acceptance of the Eurogenetic Modernism was unqualified. A majority of the drawings, straightaway, exhibit an analytical cubist linguistic mode of handling the phenomenal in representation (identified in terms of deviation from illusionistic appearance). It however, is apparent, from the exaggerated figural gestures and postures as well as from the gestural verb of lines and marks that his intentions are far from cold formal reconstruction of phenomenal appearance is governed more by the needs of expression of pent up emotion and passion. The characters he visualizes are no less than the alter egos of a lonely egotist. The dichotomy in Souza’s choice of visualistic parameters is typical of many a third-world intellectual who face walls between their existential beings and desired becoming.

Although Jagdish Swaminathan, Like Souza, is a believer of the claims of the Eurogenetic Modernisation to universal validity, he unlike Souza, would not let his belief take off from a development logic, Swami would rather validate his belief in non-representation and non-replication of the phenomenal, as the ontological truth of art, in the human spirit’s adventure with the unknown, that certain strands of Modernism had rediscovered. In the primordial human endeavor of spontaneous making of fuzzy geometrical marks on shifting sand little known birds of mind’s eyes in flight atop feather-weight rocks afloat. The monochromatic drawings, exhibited in the show, belong to a period in between Swami’s first phase of experiments with geometric mark marking on wall surface and the second period of living creature’s movements leaving marks on space; the marks which provoke thinking about the unknown creator’s intention behind every organic movement.

A fiercely liberated woman out of wedlock of almost a child marriage, Meera Mukherjee, however rejected an art education designed to treat art as an autonomous and self-contained vocation for an alienated individual. In her quest of a vocation that would connect her with the joys and sorrows of simple folks of her land, without subjecting her to the obligation of ritual obeisance, she found living traditions of arts which were open enough to innovations and adaptations. Handcrafted cheap to construct mud houses were cool and spacious enough for her to connect herself with the living technologies of reproduction of life that is dear.

The current show is of succinct statements of what the three very different artists believed art of the time to be. These dense statements often have greater clarity than their elaborate creations.

Pranabranjan Ray

Meera Mukherjee | Woman with pitcher | Bronze | 12.75 x 5.5 x 7.5 in

Meera Mukherjee | Sitar Player | Bronze | 10 x 10.5 x 5 in

Meera Mukherjee | Friends | Terracotta | 7.5 x 5.5 x 5.x5 in

Meera Mukherjee | Bull | Bronze | 6 x 14 x 6.5 in

Meera Mukherjee | The Empty bowl | Bronze | 15 x 9.5 x 7.5 in

Meera Mukherjee | Festive Mood | Bronze | 8.5 x 12 x 7.25 in

Meera Mukherjee | Children running behind horse cart | Bronze | 6.5 x 10.5 x 6.5 in

Meera Mukherjee | My home | Terracotta | 6 x 6.5 x 2.5 in

Francis Newton Souza | Untitled 15 | Watercolor | 9.5 x 7.5 in

Francis Newton Souza | Untitled 13 | Ink on paper | 11 x 8.5 in

Francis Newton Souza | Untitled 12 | Ink on paper | 11 x 8.5 in

Francis Newton Souza | Untitled 11 | Ink on paper | 7.5 x 6 in

Francis Newton Souza | Untitled 10 | Ink on paper | 7.5 x 6 in

Francis Newton Souza | Untitled 9 | Ink on paper | 10 x 8 in

Francis Newton Souza | Untitled 8 | Ink on paper | 10 x 8 in

Francis Newton Souza | Untitled 7 | Ink on Paper | 10 x 8 in

Francis Newton Souza | Untitled 6 | Ink on paper | 10 x 8 in

Francis Newton Souza | Untitled 5 | Ink on paper | 10 x 8 in

Francis Newton Souza | Untitled 4 | Ink on paper | 10.5 x 8 in

Francis Newton Souza | Untitled 3 | Ink on paper | 10 x 8 in

Francis Newton Souza | Untitled 2 | Watercolor | 10 x 8 in

Francis Newton Souza | Untitled 1 | Ink on paper | 8 x 6 in

Jagdish Swaminathan | Untitled 10 | Ink on paper | 11 x 7 in

Jagdish Swaminathan | Untitled 9 | Ink on paper | 12 x 8 in

Jagdish Swaminathan | Untitled 8 | Ink on paper | 13 x 8 in

Jagdish Swaminathan | Untitled 7 | Ink on paper | 11 x 8 in

Jagdish Swaminathan | Untitled 6 | Ink on paper | 10 x 9 in

Jagdish Swaminathan | Untitled 4 | Ink on paper | 12 x 8 in

Jagdish Swaminathan | Untitled 5 | Ink on paper | 12 x 8 in

Jagdish Swaminathan | Untitled 3 | Ink on paper | 10 x 7.5 in

Jagdish Swaminathan | Untitled 2 | Ink on paper | 11 x 8 in

Jagdish Swaminathan | Untitled 1 | Ink on paper | 7 x 6 in